Rolling Stone Magazine

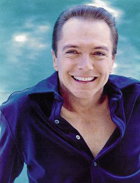

David Cassidy: Naked Lunch Box

The story of the singer, actor and songwriter beyond Keith Partridge

May 11, 1972

By Robin Green

http://www.rollingstone.com

There'll be a time when this whole thing will be over. I won't do concerts anymore, I won't wake up in the morning feeling drained, and I won't be working a punch card schedule. I've had to sing when I was hoarse. I've had them with a gun at my head, almost, saying "Record, 'cause we've gotta get the album out by Christmas!" I'll feel really good when it's over. I have an image of myself in five years. I'm living on an island. The sky is blue, the sun is shining. And I'm smiling, I'm healthy, I'm a family man. I see my skin very brown and leathery, with a bit of growth on my face. My hair is really long, with a lot of grey. I have some grey hair already.

David Cassidy

Drive over to the Hippopotamus," Henry instructed.

"Aw, Henry, let's go back to the hotel," pleaded David Cassidy, who sat slumped down in the back seat.

"Heeey," chided Henry. "We're in the Big Apple. Let's just see what's happening."

David slumped further in the joyless back seat, muttering his consent. He was exhausted, stoned and drunk, and dizzy from the antibiotics he was taking to drive away a flu. It had been a busy day two hour-long interviews in the morning; a press conference at New York City College; a rehearsal all afternoon; a session with gossip columnist Earl Wilson; and pictures for the Cancer Society. Then an impromptu tap dancing lesson in his hotel room with a lady he'd met at rehearsal that afternoon. Then dinner, dope, wine, and now this climbing in and out of the back seat of a car looking for what? New York action?

Well, he had his action and he wanted to go to sleep. But that wasn't what the others were into, except for Jill, who sat close to him. The Lincoln limousine pulled in front of the third discotheque they'd been to that evening. They hadn't stayed at the others because Henry didn't think they were quite right.

"We'll just go in and check it out," said Henry. "Just one more. If we don't dig it, we'll leave."

David mustered a small protest. "Try it," laughed Henry. "You'll like it."

So David was herded into the Hippopotamus.

"Wait here," said Ron, David's valet. "I'll go take a look."

Ron climbed the steps to a room which poured out music and cigarette smoke, lit purple and pink.

"Where do you think you're going?" demanded the doorman, who barred Ron's entrance to the room.

"You don't understand," Ron said. His voice had a bitchy edge on it now. "I'm here with Mr. Cassidy, my employer. I have to see if the place is all right. You see, there he is right there, standing with those people just inside the door. David Cassidy."

"Where?"

"Right there," Ron was almost screaming. "In the blue coat."

The doorman squinted at the slight figure in the dark hallway, then looked back at Ron.

"That's David Cassidy!" Ron said. The doorman looked at David again. He shrugged. "Who's David Cassidy?"

Only three weeks earlier that same David Cassidy had set an attendance record at the Houston Astrodome, selling 56,723 tickets to two matinees on the same day.

* * *

Baboom, Baboom, Boys, and Girls, Zing!

Madison Square Garden was filled five balconies full an hour before the matinee with 20,650 excited females the same girls who more than 20 years ago would have wept for Sinatra and 10 years ago for Elvis. Average teen age girls who keep diaries, go steady and chew gum. And many younger ones, eight- and nine-year-olds, some with their mothers. David Cassidy's audience who never miss a Partridge Family episode, who devote scrap books to him and wallpaper their bedrooms with his face and body.

Now they held up banners reading "David Spells Luv."

"I hope I brought enough Kleenex," worried a 16-year-old wearing a tight sweater and hot pants. "I'll probably cry. I cried when I got my ticket."

"Ooooh!" cried one small voice inside the hood of a pink and red snow suit. Eight-year-old wide-eyed Amanda Lewis clutched a $2.00 David Cassidy program to her undeveloped bosom. "He's so sexy."

One fan didn't know if David was sexy. "I'm a boy," explained Elliot Fain, age 11, from Forest Hills. "I think he's a very interesting person though."

The girls were there to scream. They screamed whenever so much as an equipment man mounted the stage. One news photographer approached a cluster of ladies. "Scream!" he directed. They screamed. He took a picture.

Aproned vendors coursed through with screams of their own: Posters! Programs! Hot dogs! Popcorn!

When the lights dimmed, the show's MC a fave DJ on WABC radio strutted onto the stage, long-legged and agile as a circus barker. "I just saw David backstage!" he announced.

"EEEAAHHH!" went the crowd.

"Now, when I count to three I want you to say 'Hi, David!' One, two, three!"

"HI, DA-VID!" The auditorium shook.

"And now I want you kids to show the world that children your age can behave and not go crazy. Yell and scream, but stay in your seats. Let me hear you say 'I will.' One, two, three!"

* * *

In a windowless cinderblock dressing room, all David's people were assembled. Wes Farell, record producer; Ruth Aarons, manager; Jim Flood, PR man; Steve Wax Erman. Sam Hymen, David's roommate, Ron the valet, Henry Diltz, pop photographer, Steve Alsberg, road-manager. No Jack Cassidy, David's father, but Shirley Jones, his stepmother, with two of her three sons, and his mother Evelyn Ward with David's grandfather, 84 years old, in a grey three-piece suit.

In a corner, a pile of gifts from fans four feet high: stuffed animals, plastic flowers, incense and scented candles, shirts and hand-printed messages of undying love.

David signed autographs for promoters' and policemen's daughters, and chatted with well wishers. It was a high moment for him; a triumph, he called it. "Here I am," he said. "I've arrived."

"Think about it," said Henry Diltz. "The karma is fantastic. David was an actor, looking for a break, and then this Partridge Family TV show comes along. He wasn't a singer, but he evolved really nicely into one. Take the Stones, or Cream. After being into folk music, the blues, and rock and roll for 10, 12 years, they fill Madison Square Garden. Well, David's filling it, too, and he's only been singing in front of people for a year!"

Minutes before showtime, Ron helped David into his costume, a $500 white crepe jump suit slit to the navel and decorated with fringe, beads, bells and sequins around the waist.

"I wish," said David, "that anyone who has ever put down someone in my situation the Beatles, or Presley or anyone I wish that they could be where I am, could jump into my white suit for just one day. It's such a rush, they'd never come down to think about it.

"It's a high going out on that stage. You look around and it's all there for you, people loving you like that. My friends are there with me, I'm doing what I love to do most, singing and I'm singing for people who would rather have me sing than anybody else in the world.

"There's one song I do, 'I Woke Up in Love This Morning,' and I find a little place where I can sort of point to them. And they each think I mean them, and I do. Whew, I can't wait. Let me get out there. Let me do it!"

David sang into the mirror as he applied pancake make-up to his face, chest and arms. He said he didn't think of anything before a concert. "I'm in a state of, 'Well, here I go,' like a runner before a race, an athlete before he takes the big dive. The roll of the drums, baboom, baboom, and then, 'Ladies and Gentlemen, boys and girls!' And I take the baton and zing...!"

Flanked by his valet and his road manager, David was off and running. He leapt onto the stage, welcomed by a blood curdling screech. The continuous blinking of flash bulbs gave the place a strobelit effect. "I love you, I love you," David screamed back at them. "I love everybody."

On stage this mild, quiet guy was transformed into a glistening white superstar. He gave it everything, his 5'7", 125-poung body had. Like a young and healthy animal of no particular gender he moved as he sang, in a graceful, almost choreographed way.

"I never get tired of watching David's act," said his roommate Sam Hyment, looking on from the sidelines. "And I've seen it 50, 100 times. Something's happening out there. The white costume, the big band behind him." The band played perfectly, wearing sedate matching maroon blazers. "I like to watch the audience, too, they're so turned on and happy."

In the first row, Shirley Jones sat with David's family. "It's like a revival meeting," she said, "the way he excites the audience, then calms them down."

Fans tossed stuffed animals and dolls onto the stage, and one girl managed somehow to elude guards and climb up there herself. Once there, she froze. David jumped when he noticed her, a plump girl in a blue chemise. Gracefully, he took her hand and kissed her cheek.

Though no one fainted, as 24 had in Detroit, the energy was high. The girls went wild in place. The young ones grew restless when David crooned the slower ballads in a small, but soothing voice. Many older girls wept.

If David was emanating heavy vibes, they escaped one 24-year-old observer. Jill watched the show on a backstage TV screen. "It's so weird," she said. "Last night, he was really nice. He was a really good fuck." Jill shook her head. "But seeing him doing his act, I can't believe it's the same person. This act is so Las Vegas. He's like a male Ann-Margret."

Twenty thousand girls were satisfied, though, transfixed by their idol. When the hour set was over, they sat in darkness and groaned in disappointment. But not for long. When the lights went up, they recovered and set to furious but business-like pursuit of their fantasy. Guards blocked off the backstage area, but some fans were small enough to race under their arms and between their legs, overturning one cop.

Finally, they swarmed through, searching for David, who had made good his frantic escape covered with a blanket on the back seat floor of a Japanese sedan. One vendor sold programs along the escape route, getting in a few last minute sales.

* * *

Twitchy Thighs and Sticky Seats

In two years, David Cassidy has swept hurricane-like into the pre-pubescent lives of millions of American girls. Leaving: six and a half million long-playing albums and singles; 44 television programs; David Cassidy lunch boxes; David Cassidy bubble gum; David Cassidy coloring books and David Cassidy pens; not to mention several millions of teen magazines, wall stickers, love beads, posters and photo albums. Among many things, including those wet theater seats.

As David himself puts it, "This is very filthy, but when the hall empties out after one of my concerts, those girls leave behind them thousands of sticky seats."

Virtually unknown in the older world of rock audiences, David is an idol to television multitudes and teenage millions. The rise to fame began more than two years ago when he appeared in television programs like Ironside, Bonanza and Marcus Welby, MD. And when he landed the role of a dying boy on Medical Center, he unmistakably began to capture viewers' hearts. Then came Keith Partridge, a weekly situation comdy role in The Partridge Family.

When The Partridge Family started, David was 20 years old. But with his exceptionally pretty face and tiny voice, he passed as the bouncy 16-year-old son in a family of four children who lived in the suburbs and made their living as a rock and roll band.

Only two years before, the show's producers had created the Monkees. With The Partridge Family they planned to dub the singing when the band performed, but they soon discovered to the delight and surprise of everyone that David himself could sing.

Soon, the television company began putting out Partridge Family records, which sold well. Soon enough, David emerged as a solo performer, cutting his own records, on tour with his own band.

***"For many of the girls it's the first time their little thighs get twitchy," opined Steve Alsberg, David's road manager, as he hit down his fourth bloody mary of the flight from New York to Bangor, Maine. Steve, a 28-year-old aging surfer and an L.A. native, had been a road manager for eight years, shepherding Three Dog Night, the Turtles, the Flying Burrito Brothers and Les McCann on concert tours. Working for Cassidy, he said, was the least hassled, because the tours were more Businesslike. "These people are professionals," he said of David's 15-member band, who now sat in the coach section. "They're studio musicians, men in their 30s, mostly [except for David's friend Cookie, 21, who plays guitar]. This is an easy gig for them. They don't have to do shit. They get off the plane, on a bus, do the gig, and then back again. And they're not prima donnas. All they want is to put on a satisfying show."

Tucked into the first class section looking much smaller than his television image, David Cassidy himself ordered a glass of milk.

"I've been sick all week with the flu," David explained, "and I think it's turning into a cold."

Illness notwithstanding, he had played Madison Square Garden the day before. And it had been sold out for his concert only three days after tickets had gone on sale three weeks earlier.

"Two years ago, I was getting food stamps," he marveled, this 22-year-old man set in a boy's body with a face so pretty that men do doubletakes on his posters. He fidgeted in his seat and regarded his new companion.

"You know, when I first was told about this article, I wanted to smile and say, 'I really don't care to talk to you.' I expected it would be a put-down. I mean, your readers are not going to come and see me, they're not going to buy my records. Even an article that says David Cassidy isn't so lame, or maybe he can really sing, it's not going to affect them really. They're still going to think I'm an asshole.

"I read in Rolling Stone once an article about the Jackson Five. It said they were the black answer to teenybopper idols, but that they had soul unlike those white sucaryl teen throbs like Bobby Sherman and David Cassidy. I read that over five times, and I still could not believe it.

"I had some hostility towards you, and I still do probably. The magazine is very anti-me and anything I have going for me like commercialism and all that stuff.

"I'm afraid of it 'cause it attacked me. It put a knife into me," he stabbed at his chest with a fist. "And I bled. I went omph, that hurt. So I take the knife out and I bandage myself up and I say, OK, now I'm afraid of that, right? That stuck me once and shived me once and it wasn't really even about me.

"So I'm very defensive about Rolling Stone. I guess that's kind of a fucked way to be." He sat back and sighed. "But I would really dig reading something about me that wasn't, you know, the same old bullshit."

* * *

A Fig Leaf Falls: David Stands Naked

Ruth Aarons, who manages David, has been in business 20 years, and in show business all her life. Her father, Alfred E. Aarons, was one of Broadway's biggest producers in the early 1900s. Her oldest brother, Alex, with his partner, Vinton Freedley, produced all of George Gershwin's shows on Broadway, among them Funny Face, Lady Be Good and Girl Crazy. Alex and Vinton owned the Alvin Theater, a bastion of New York legitimate stage, which has since been sold. "I'm going to buy it back," said Ruth, a small, boyish woman in a trim dutch boy hairdo, "when I get crazy enough."

Before starting Aarons Management with her other brother Lisle in 1951, Miss Aarons spent five years playing ping-pong. As a world tennis table champion she gave exhibition games at the Roxy Theater, the Rainbow Room, and London's Wembley Stadium. When she tired of that, Ruth wrote song lyrics, and from that got into managing one of her clients, Celeste Holmes. Her management company grew, with offices in New York and Los Angeles, taking on Shirley Jones, Jack Cassidy, George Chakiris, and now David.

She moved to Los Angeles in 1967, where she lives on an estate in Beverly Hills large enough to house two dogs, two horses, and a pony, as well as herself and the offices of Aarons Management.

"The only things that really interest me in the world are Tinkerbell and Captain Hook," said this shrewd, professional woman, referring to the tiny Yorkshire Terrier in her arms and a fat black dog playing near the stables.

"I've known David since he was eight," she began, settling into a plaid couch in the livingroom of her country English style house while Clide the black butler served cool drinks and lunch. "I used to watch him play baseball in the Little League here in Los Angeles.

"It wasn't until David was 18, I think it was, that I became aware that he wanted to act. His father, Jack Cassidy, came to me we were in New York at the time and said, 'Ruth, David doesn't want to go to college. He wants to go into the business. As long as he's going in, you better keep an eye on him.'

"So David took some coaching lessons how to project, that sort of thing and a course in elocution with Philip Burton, Richard's father. Then he got a small part in a Broadway play called Fig Leaves Are Falling."

Miss Aarons rose suddenly, circled around in place, and sat down again, tucking one leg under her. Her dog Tink echoed this action.

"Well, Fig Leaves folded like a tent," she recalled. "Then I told David. 'Look, you've got two ways to go: you can stay here in New York for seven years and learn to act. Or,' I told him, 'you can come back to Los Angeles and be a star.'"

* * *

"I was an actor," David explained later, thinking back to his decision to forget Broadway and return to Hollywood. "I was out to earn the bucks. I wanted to be a working actor one who works all the time, who other actors look at and say, 'Well, he's pretty good.' Honestly, my goal was not to be a star."

Five weeks after his return to Hollywood he went from earning $150 a day to television guest-star roles. And then came the script for The Partridge Family. "When I first read the script, I thought it was terrible," David recalled. "I was thinking about saying these dumb lines, like 'Gee, Mom, can I borrow the keys to the car.' I just couldn't bring myself to do it after doing all those heavy things I'd done.

"I called Ruth and said, 'You gotta be kidding with this.' And she said, 'Read it over again and call me back.' Well, I'm so soft. I read it over twice and then I called her back and I said, 'I guess it's not so bad.' Only because I'd gotten used to it."

And he had the same reaction to the music he was being asked to perform, first as part of The Partridge Family and later on his own. "When I first got in the studio, I said to the producer, Wes Farrell, 'I don't want to cut bubble gum records.' And he said, 'No, man, we're not going to cut bubble gum records.' Me and my friend Cookie were jamming at the time, the blues, and all of a sudden I'm gonna sing, 'I Think I Love You!'"

At first, radio stations hadn't liked the song either. But it has now sold over five million copies. "When that record came out it was only Wes and Larry Uttal, head of Bell Records, who thought it was going to be a smash.

"What happened with that record was we got secondary air play on it, small towns. The primary stations didn't want it. They said, 'Let the TV show break it,' which I can understand."

Finally one town, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, played the record, and it went from 40 to one in two days.

"Now everybody cuts it. Percy Faith, the Boston Pops. And it was written for me. I've got good writers writing for me. "I want people to know that I like to sing that song. I stand naked that's the best word I can think of and say 'This is how I am.'"

* * *

Soul on Ice Cream

From the window of the Old World Restaurant on Sunset Strip, 29-year-old pop photographer Henry Diltz could see four billboards with photographs he'd taken. Most prominent in the view was the billboard of David Cassidy in a lacy white shirt. It advertised his first solo album, Cherish.

"I'd been sent down to The Partridge Family set to take pictures of David for a fan magazine," Henry recalled. "There are millions of photographers there to get David Cassidy shots, right? The best thing to get is shirt changes, because if you get four or five different shirt changes, that'll go for four or five different issues. After I'd been around for a while and got to know him, I got reluctant to ask him to do this bullshit. So one day I was on the phone with Don Berrigan, my editor. I was telling him, 'Listen, David doesn't feel like trying on the shirts you sent over.' And he said, 'Well, tell him we'll give him something. What does he want? A camera?' So I told David that and he said, 'Great, sold, you got it.'

"And that's nice. It's a little tip. That's saying. 'Hey, if you'll consent to this bullshit, I'll make it worth your while by giving you this Nikon.' So every shirt change we gave him another lens. It's the same as anything, just buying and selling."

Henry paused and glanced up at his artwork across the street. "Donny Osmond of the Osmond Brothers is the new idol now. They just bought Donny a Super Eight Camera. This year David won't be getting any more equipment because he's on his way out."

* * *

"Is that Star?" David asked Henry across the aisel of the airplane. "Let me see it." David leafed through the teen magazine. "Aw, look at this, Henry, this is disgusting. 'A Bubble Bath with Butch.' And this one, 'Pets of the Past.'" He held up a page filled with the face of a young star and an Irish Setter.

"I wonder where this guy's head is at," said David, shaking his head in outrage.

"He's a rascal," Henry replied. "He's a magazine publisher!"

"This time they've gone too far!" He had come across a contest to find his face in his junior high class picture. "They could at least have asked me! That's digging too deep!"

"Oh, he doesn't mean any harm," consoled Henry. "He won't do anything if you don't want. If you say to him, 'Hey, man, I don't like that,' he won't do it. But if you say, 'Don't do that!' he'll say, 'Ah hah!'"

"Well that really bothers me. I don't need all this. I've got my cake. This is just the icing now."

"You're beautiful when you're mad," laughed Henry.

"I had never read a fan magazine before all this," David was saying, "I didn't know what a fan magazine was until they called me up and said, 'This is gonna be real good for your career, kid.' It was just after I had done my first TV things. Three shows, and they're on me like vultures.

"At first, I said, 'too much.' I bought a few of them and took them home. I saw Bobby Sherman had a thing selling love beads. I said this is a weird trip. I mean, I gotta look at myself in the mirror in the morning and it was like, I can't do it when they're writing 'David's dream wife,' and 'Kiss David.' I had a bad taste in my mouth from it. I didn't want to be that.

"So I went to them and I said, 'Listen, do me a favor. Don't put me on the cover. Could you just not do that.' Honest, I said this. This was the only major thing I ever did that slowed down the momentum." He laughed a bitter sort of laugh.

"But it was foolish, because you have no control of these things at all. I'm sure they ended up laughing at me, snickering to themselves, saying 'how ridiculous this fellow is.'

"Now I don't read them. It's a side effect that just eats away at me. I don't read them, and I don't see them. Don't tell me about them, 'cause I don' wanna know. I'm on too much of a good trip to bring myself down about stuff that's not real."

But the David Cassidy love beads, the David Cassidy bubble gum, and other merchandise now for sale? Had he found a way to adjust to that, too?

"Listen, if they're going to buy lunch boxes, they might as well buy David Cassidy lunch boxes."

* * *

Being mobbed was another occupational hazard that David was unable to adjust to. His fear sometimes caused him to behave in strange ways. Henry Diltz recalled a vacation he and David had gone on, to Hawaii.

"We got off the plane and he hiked his jacket up over his ears and stuck his head way down. I said, "David, there's nobody who knows you're coming here!' He was calling more attention by walking that way. People were saying, "Look at that weird guy in the little hat and sunglasses, hiding his head! But he wouldn't listen. He said he wasn't taking any chances. That if one person saw him, that would lead to three and then 15 and then 100, and he's afraid of that."

"I've been hurt a couple of times," David explained. "I've been scratched on my arms and chest, and face. Once I was hit in the face with an Instamatic camera."

The worst incident had been in Cleveland after a concert.

"Security wasn't good enough and they said, 'Listen, you may not make it.' And I didn't. It happened really fast. They crowded around and came down on top of me.

"I got down on my hands and knees and started crawling. Someone who worked for the Monkees told me to do that. And it worked. They didn't know how to deal with me in that position.

"See, what they want is your hair. They want to grab your hair. And my scalp is so sensitive, I get crazy when anybody grabs my hair. I can just cry. I can cry very easily."

* * *

"You have to pay dues for everything, whatever you do," David sighed, after giving autographs to the flight crew and various passengers. "I must have signed 80 thousand. In the beginning I'd do two thousand at once at some publicity thing at a supermarket.

"Every time I get asked I think I'm going to scream. Please, don't ask me again! My hand is falling off! The thing that irritates me is that they never want it for themselves. It's never, 'I really like you. I'd really like your autograph.' It's always, 'My daughter would never forgive me,'" David mimicked a New York accent. "'Also, my friend Joe needs two for his kids or they won't let him in the house.' I'd dig it if someone would come up and just say 'sign.'" "I always do it, though. I mean, I can't say, 'You motherfucker, you're 8000th today!' To him it's a big thing, obviously I bring him some joy!"

On the question of politics, David said that he hadn't any. "I don't listen to the news or read newspapers. I don't know what's going on in this world, or why I should vote for George McGovern or Richard Nixon. I don't have enough time.

"I read in one fan magazine that I was very self-centered. And I am. I work for me, 18 hours a day. It's my gig. So I don't have time to get a point of view.

But I've become accustomed now to handling whatever comes at me," continued the voice in the young body. "Like that press conference at the airport? I thought to myself, 'How long do I have to sit here and handle this?' It's always the same thing."

He held his fist up to his face like a microphone. "'How do you feel about the war in Vietnam?' I'm so tired of answering that question. Or, 'Being as you have an influence on young folks today, what advice do you have for them about drugs?' Aw, shit, man, take drugs."

At the press conference, David had sat with a television cameras trained on him, answering questions from a television reporter, who with microphone in hand, knelt at David's feet.

"What advice do you have for the youth today?"

"What's right for me," David had said, "is not necessarily right for them."

* * *

A Fig Leaf Doesn't Fall

Both teenaged girls wore hot pants, silver stars pasted on their red-polka-dot cheeks under heavily painted eyes. The two had camped out in front of the elevator door on the sixth floor of the Plaza Hotel all evening, waiting for David to return to his suite. When he appeared with his entourage, the girls rose. They didn't rush to David, but ran instead into each others' arms where, according to some apparent plan, they arranged themselves in a provocative pose. They smiled.

"Hi," David smiled. "What're you girls up to?"

"You!" they squealed, and kissed each other passionately.

Arms around each other, the shorter girl moved one leg between the other's thigh, and with her free hand began to caress her friend's bosom. David took Jill's arm and led her past them down the hall.

The two girls stared after him, disappointed. They pleaded with Henry to intercede for them.

"David," Henry ran down the hall. "Where are you going?"

"Aw, Henry," David said, 'Chicks like that don't turn me on."

Henry talked to him in earnest tones, gesturing occasionally towards the two girls who smiled hopefully at David each time Henry pointed their way.

"But Henry, I mean, after I got done making love to that, I'd feel shitty. I couldn't look at them. I couldn't wait to get them out of my bed so I wouldn't have to see them there, and face them, and myself, too."

When David emerged from his hotel room the next morning he saw that the two bizarre would-be groupies still stood draped around each other leaning against a wall outside the sixth floor elevator door. "You think they were there all night?" David asked Henry in the limousine en route to Madison Square Garden.

"Naw," said Henry. "I let them camp out in my room on the floor. They were strange little girls. I had to drag it out of them, but they're from New Jersey. Just two ordinary girls during the week. The big one with the moustache is a telephone operator, and the little feminine one works in a store."

"Oh, no!" groaned David, "there they are in that cab behind us."

From the yellow cab following them they could see two excited females waving and smiling. "Get rid of them Caesar. See if you can lose them." David's voice was urgent. "I don't want them around me. I don't want them near the dressing room. My family is going to be there."

* * *

Prime Times

David Bruce Cassidy was born on April 12th, 1950 in Englewood, New Jersey. He moved to Hollywood with his mother after his parents, Broadway actors Evelyn Ward and Jack Cassidy, were divorced when he was five.

"I had a lot of rejection from my father when I was young," recalls David. "I never saw him after he divorced me and my mother. I wouldn't hear from him for a year. I don't feel any hostility towards him. I'm a friend of his now. But a little boy shouldn't have been shunned like that."

He had a normal, baseball playing childhood in Los Angeles, until he was 14 and became a bicycle thief. "I had a bike shop in my garage. I'd be walking home from school and I'd see a bike sitting there, and I'd rip it off and drive it home. I'd paint it or do something neat to it. I ended up returning a lot of them, but I sure must have caused those people a lot of grief."

It was around that time that David started seeing a psychiatrist. He's been seeing one off and on since. Also, he started experimenting with drugs. "I didn't know who I was, and I did a lot of fucking around, experimenting not smack, but grass and speed and psychedelics. I had some bad trips tripping for kicks in the worst, most paranoid places." He was among those 16-year-olds who in 1967 went up to Haight-Ashbury to see what was going on.

"But I wasn't taking drugs seriously. I didn't want to be a junkie. A few of my friends died, committed suicide actually.

"Then I came down with mononucleosis and spent three months in the house. No socializing, no getting high thinking. And I found out I cared a lot about myself. I wanted to achieve something, to do something with my life."

He went back to school. "I didn't let myself get into a rut after graduation. I gave myself a two-week vacation, and then went to New York." He got his first job, working part time in the mailroom of a textile firm in New York's West Side garment district, and took acting lessons at night.

And he's worked ever since, except for an occasional vacation, and a three-week spell last summer when his exhausting schedule caught up with him. "I look at that scar on my stomach," he said, "and I think, if I didn't have it I'd be dead.

It happened after a concert at Wildwood, New Jersey. I came back to L.A. on Sunday night to get a few hours of sleep. I had to be at The Partridge Family set at 6 AM. Well, I woke up at three in the morning, screaming in pain, holding my stomach, banging my head against the wall trying to make something else hurt until the doctor got there.

"It was gravel and stuff, from a bad diet or something, in my gall bladder. Rather than take out the stones, they removed the whole thing."

David lives in a huge house in Encino, California, on two acres with fruit trees. It is a retreat from a hard schedule of filming five days a week, recording at night, and concert tours on weekends.

"Whenever I go over to see him, he opens the door and he's alone," observed Henry Diltz. "He leads a bachelor sort of existence. I've watched him eat dinner a can of peaches, a piece of bread. I mean, like at Steven Stills' house there were always four or five ladies living there, hanging out in the kitchen, always making some groovy organic feast. Girls drop over and make themselves useful so that they can get to stay. They drop by and say, 'Where's the vacuum cleaner.' They start to vacuum and people say, 'Hey, she's together. She's groovy. Keep her around, She knows how to vacuum.'"

"There's nothing like that at David's house. He prefers to be alone. I'm sure he could have his house full of girls if he'd rather, but he's a quiet sort of guy.

"Like the trip to Europe last winter. He wanted to go totally alone. Every magazine offered to pay his way and mine, and buy him a VW camper. We talked about it and David said no, because then he'd have to worry about whether he got a little zit or something. I mean, I could go hang out with David Crosby on his boat and he'd run around naked. He wouldn't care. But David's serious about his career, and his image partly because of the family thing, Ruth and Shirley and being Jack Cassidy's boy. And he has that image of Keith Partridge to uphold.

"And he's not as old as David Crosby. He hasn't been into the rock and roll world. It's different on the road, too. It's not motels and groupies. It's very fastpaced and business-like. That other thing will come later for David. Remember his audience is still 11 years old."

Next to David's white Corvette in the driveway of his spanish style house is Sam Hymen's VW Bug. Sam is David's friend of ten years and now lives in a small cottage in the backyard. Sam lays naked, long and slender, dark-haired and dark-eyed, sunning himself next to the swimming pool, recalling the early days of his friendship with David.

At University High School in Hollywood, before David was expelled for cutting 102 of one semester's classes, he and Sam had belonged to the same "social club." "Those clubs were either football clubs or fighting clubs. We were both wimps, so we belonged to the fighting club for security. We would have been killed playing football.

"At the end of the ninth grade we started tripping with drugs. David was never really sold on LSD, he didn't have that many good trips. He was more into hash. He always had more hash than anyone else I knew."

After David returned from New York he lived with his mother again. Then he and Sam moved out of their parents' homes and into a house in the Hollywood Hills. "I was working as a film editor," Sam recalled, "and David was just starting to happen as an actor. He never talked about it much, but he'd stay up at night alone, thinking it all out. He kept a lot to himself and still does."

David doesn't have many hobbies, though he skies and goes scuba diving when he can. He spends most of his time off playing the guitar, sitting on his amp, at his new house in Encino listening to Steven Stills, Neil Young and David Crosby, imitating the songs. And writing songs of his own. To date, David has recorded only one of them: "Ricky's Tune," a song about his recently deceased dog.

"I think David's a little frustrated with what he's doing now on The Partridge Family. He can't demonstrate much acting ability doing that. He knows he has talent; he wants to develop it and direct it to his peers and be accepted by them. That's what he's trying for now."

"He doesn't have an old lady at the moment." Sam continued. "He doesn't have time, really. We were just talking about where we'd like to be in a year or two: get some land, eat fruit, make music, go scubadiving. We'd still produce artistically. But we both agreed that it would all be worthless if you didn't have a lady. Good friends as we are, we can only fill so much of each others needs. Some people can be complete with someone in their own sex, but I can't and neither can David."

Sam turned over to sun his other side. "I think what's made it a nice relationship with David is that I've never relied on him. I've stayed strictly independent. I have to work for everything I get. David's respected that." Last April, Sam quit his film editor job to merchandise posters and programs at David's concerts.

Sam paused, thoughtful for a minute. "The merchandising trip is my reality now," he went on. "It may seem totally lame and fucked up to someone else, but it's my life. I know I'll always be in business, he chuckled. "'cause I love money, and in this business you've got to make it when you can."

* * *

"An unhappy artist never works out, longevity-wise."

According to David Cassidy's biography sheet, put out by his public relations firm: "Most artists, overwhelmed by their swift elevation to love object status, fail to provide for that inevitable rainy day when fans regroup around next year's superstar. And the artist finds himself a has-been at 21. Not so, David Cassidy."

At least, that's what his management is hoping. "People say we have to hang on to his youth audience," said Ruth Aarons. "But that's like Peter Pan, and David is maturing. Of course, the long haul is hardest to sustain. But with a good proper structure behind him, David will continue to grow. I depend on his instinct and his following to tell me where to place him in this market."

His management was looking into movies and TV specials "with meaning" which would appeal to older audiences. And David would continue recording.

"To me," Ruth went on, "David is the inherent comsummate entertainer. He has an instinctive command of audiences. The way he leaps out and bounces around on the stage, his little yellings of 'I love you' it's exciting, and theatrically effective. He projects a joyful, affirmative sexual appeal. He does not infer destruction. Like Sinatra in the Forties he has that touchable, vulnerable, clean attraction.

"He is not, as some critics say, a hoax that's being foisted on the public a figment of someone's imaginings, a put-on. He's not a make believe performer.

"And no matter what happens, he still has done something few have achieved."

Jim Flood, the man in charge of David's publicity, is among those interested in helping David grow. To take the job handling David, Flood had dropped his other clients: Jerry Lewis, Mary Tyler Moore, to name a few.

"This whole thing with David is for me, personally, a calculated risk," said Flood. "With all the time I've invested in David this last year, I'll still make half the money I used to. It's a gamble. It could not work out. But it will. And there's no way David will wind up a broke rock star."

Besides Ruth and Jim to look out for him, David also has a financial advisor, Lee Bush. At first, Bush refused to divulge how much the teen idol business brought David last year, or to predict what he would make in the next year.

"People think in terms of gross," said the white-haired, cigar-chewing Bush. "Like at Madison Square Garden, they grossed $130,000. But there were huge expenses." Profits from the concerts go, not to David, but to Daru Incorporated, a corporation whose name combines David's with Ruth Aarons!'

"Besides expenses," Bush continued expenses such as David's weekly allowance of $150 "don't forget the government is one of his partners." Anyone who makes over $100,000 a year is taxed 50 percent on the first $100,000 and 70 percent on every $100,000 after that by the federal government. And then there's a California tax of 11 percent. "But it's a way of life you learn to live with," he sighed.

To help him live with this way of life, Bush invests David's money in municipal bonds, which yield only 41/2 percent interest annually, but are tax-free investments. Also, David owns oil stock, and is looking into buying land in Hawaii.

"I will say, in effect," Bush finally said, "that last year David made a quarter million dollars, and should he keep his health, and keep working, we look forward to another good year."

* * *

Smoking a joint and drinking wine ordered from room service at the Plaza Hotel, David watched the March 10th episode of The Partridge Family.

Keith and his family were driving to the country for a week's vacation from their busy schedules as rock and roll stars. En route, their psychedelic painted bus breaks down. They seek help from a country couple, who recognize them and plot to keep them there so that they'll perform at a benefit for a neighboring Indian reservation.

"Watch," David predicted. "Here's where I do my pouting schtick. I always have to do one of these things."

On the screen, Keith is annoyed at the delay, and puts up a fuss when his mother suggests he take his younger brother Danny fishing. While cleaning the fish in their captor's garage, Keith finds a case of the stuff needed to repair their bus. He realizes that the couple is lying to them. Holding one of the fish he has caught in his hand, he says to Danny, "There's something fishy here." Laughter, on the television and from David's corner.

Keith stalks into the couple's house to confront them. But the two still hide their intentions, and Keith is chastised by his mother for being suspicious.

The next day, the couple takes The Partridge Family to the Indian reservation, where they see the plight of the Indians.

"Someone should do something," says Keith's mother.

"That's what everybody says," moralized the country woman.

Keith's mother apologizes and asks what she can do to help.

"Well," replies the woman, "there is going to be a fair for the Indians this afternoon. Perhaps you could entertain."

Just then, the younger son, Danny, finds a leaflet announcing that his family was scheduled to perform that afternoon. Everyone laughs, realizing that there has indeed been a plot all along.

The plot thickens when The Partridge Family manager finds one of the leaflets, which has reached him somehow, in Las Vegas. He drives out to prevent the concert which is against the terms of the family's contract. Discovering this, the couple send the manager on a wild goose chase.

"Watch this," David laughed. "This is really funny."

In full color the manager is scared foolish by a band of Indians pretending to be on the warpath. Meanwhile, The Partridge Family performs on a stage atop their bus, and everything works out for the best.

* * *

"Well," said Bob Claver, executive producer of The Partridge Family, "Let's face it. No TV program is going in any time capsule. But we try to make them as good as we can, under the circumstances.

"The show's not meant to be realistic. It's entertainment. Viewers would like to be in that family. The characters are good looking, they're in show business, and they seem not to have the problems that plague most people. We deal in fantasy, and I can't see where it's all so ruinous." Especially since, he explained, they try to instill a moral message in every program.

Claver puffed thoughtfully on a Pall Mall, relaxed on the couch of his plush office at Screen Gems in Hollywood. Behind him. the wall was decorated with full color TV Guide portraits of faces unrecognizable to anybody but a TV buff. Claver explained they were the stars of Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, The FlyingNun, The Bobby Sherman Show, and The Partridge Family.

Claver said he likes working with David. "He's willing to play a fool. Every once in a while Shirley Jones, who plays the mother, will object to something in a script. She'll say, 'A mother would not do this.' But David, he never objects."

When the idea for a show based on the real-life Cowsills came up, the producers, Claver said, planned to put out records and merchandise as they had for the Monkees, the Flying Nun and other properties.

According to Steve Wax, public relations man for Bell Records, the records provide the greatest revenue for Columbia, which owns Bell as well as Screen Gems.

Wes Farrel was assigned as producer to create a sound for the show. Steve Wax put a record on his office stereo, "so you can get an idea soundwise what I'm talking about."

Through a speaker in the ceiling came David's wispy voice.

I am a clown, I am a clown,

You'll always see me smile,

You'll never see me frown,

Sometimes my scenes are good,

Sometimes they're bad,

Not funny ha ha; funny sad.

I am a clown, look at the clown,

Always a laughing face,

Whenever you're around,

Always the same routine,

I never change,

Not funny ho, ho; funny strange.

"That song is too heavy for ten-and twelve-year-olds," said Wax. "But at FM stations, the David Cassidy name is not accepted. They're really concerned with images, not sound. I think it's hypocrisy."

"Bubble gum music?" said Wax. "You've got to remember that good and bad is a relative term. People say to me, how can you promote that stuff? But I'm paid to do a job, so what do my personal likes have to do with it? If that's what the people want, how can I deny it to them?"

Wax said Bell had invested a lot of time and money on David because they expect him to be a big act for them. Now, he said, they want him to develop as an artist. "Not too fast, though. If you change your image too fast, like Bobby Darin tried to do when he went off to Big Sur to write his own material, your following will rebel.

"And," he added, "if we try to make him into something he's not, we'll have an unhappy artist, and an unhappy artist never works out, longevity-wise."

* * *

A Fern Unfolds

"David's passed his peak already," calculated Gloria Stavers as she sat behind the grey metal desk from which she edits 16Magazine, the premier teen publication with a monthly readership estimated at 6,500,000. "But his effect will last until the end of the year."

Gloria's hair is pulled severely into a high ponytail. She is wearing black slacks, sneakers, and a camelhair sweater.

"I don't always look this way," she explained in a hard voice bearing traces of her North Carolina upbringing. "I can actually be very charming and well-groomed when I need to be."

Gloria Stavers won't reveal her age. She doesn't want her readers to know. She has been in the teen mag business for 15 years now. Her's, 16, is the undisputed leader in the field, possibly because of her enthusiasm. She reads every one of the fan letters that come to her office each week, to be stored by the thousands in shopping bags stacked in rows in the drab reception room of her stale-smelling office at 745 Fifth Avenue in New York. The average age of her readers is 13-1/2 years, 99 percent between ages 11 to 15.

"It's an oral age for the girls. Their idea of sex is malts and hamburgers, a kiss. It's a romantic thing, not physical nor orgiastic. They think of their idol as a teddy bear, a blanket, a cuddly thing. "16 is a fantasy escape for them. When you're 12 years old and you hate your mom and dad and you can't do anything right, and if you're lucky you have a best girlfriend, you turn to 16. And we give them something to fantasize about.

"We also turn them on to subtler stuff. We offer gospel and jazz and we plug Siddhartha and Blake, which Dylan suggested. He also suggested Naked Lunch, but we censored that. As Dylan said to me, we're sort of like a candy store."

Her voice softens as she speaks of Dylan. "But he said, 'The truth is where the truth is, and it's sometimes in the candy store.'"

She returned to her chair. She leaned back, eyes narrowed, and considered the full-color, shirtless, hairless chest of the David Cassidy poster on the wall opposite her. 16 never retouched his pictures, she said, pimples notwithstanding.

"It was two, two and a half years ago when I first met David. I'd heard of him before that. It was earlier in 1970, six months before Screen Gems showed the pilot for The Partridge Family. It was the kids, in their letters, that first brought him to my attention. He had done a bit on Medical Center as a hemophiliac I remember what it was because all their letters had it spelled wrong."

At that time, explained Gloria, there was a lull in the teen idol field. Long ago there had been Elvis, Ricky Nelson, Fabian, Bobby Rydell and Frankie Avalon. Then there had been a "blond period": Richard Chamberlain and David McCallum of The Man From Uncle, followed by the Beatles, The Dave Clark Five and the Stones. And then, the Monkees.

"The Monkees were the biggest," she says. "They got 14,000 letters a day. David only got 3000 at his peak."

Just then an office assistant entered, a pale young man with unnaturally yellow hair. He handed her a letter.

"What the hell is this?" she yelled, waving the letter at the fellow. "Where the hell did they get this 16 stationery?"

The boy accepted her rage impassively. "No teenagers in the office, you hear? They end up wrecking the place. Just wait until summer when they ain't got nothing to do. They come in here ..."

The fans are always trying to get to Gloria, which was why her office was hidden behind an unmarked door on a different floor then listed in the office building's directory. She was calm again. "Where was I? Oh, the Monkees. Did you know they are suing Screen Gems? I can't remember the exact details. Wait, I've got the clipping around here somewhere."

She rose again and flew around the office, leafing through stacks of letters, old magazines, and xeroxes of news items. "Ahah, here it is."

"David Jones and Mickey Dolenz," she quoted, "are suing Screen Gems for $20,000,000. The plaintiffs charge breach of contract, fraud, deceit, misrepresentation, conspiracy to deny them royalties for discs, merchandising, song writing and producer royalties, and also personal appearance coin."

Gloria explained that Screen Gems, (owned by Columbia Pictures), makes most of its money from merchandising. She stated that income from merchandising the Monkees and other Screen Gems properties what with records, posters, and various other items had once saved Columbia Pictures from going under. But the Monkees saw none of that money. They were paid a weekly salary, and ended up with nothing at all, which is why they were suing.

Screen Gems also holds the rights, Gloria said, to David Cassidy. "David is on strings with Screen Gems," she said, "But that's the game. David was complaining about that one day, and I said,'David, nobody twisted your arm and made you sign the fucking contract. You wanted this. If the chain fits, rattle it,' I told him. I remember he laughed sheepishly and said, 'rattle, rattle.' There's no crap with David."

She paused for a moment. "Where was I? Oh, yes. The TV pilot. Well, when I saw The Partridge Family pilot, this was in 1970, I said here we go again. I'd been waiting for him for one and a half years. So I got all my guns ready you know, we have certain standard material a master questionnaire. I can't show it to you, though. I've got enough of those creeps from other magazines copying my stuff already. But all I need is to see David twice a year. I can get so much stuff out of him.

"David is very well-managed, and that's important. These idols don't last long unless they are. The fans grow up, their crushes don't last. Coloner Parker made Elvis last 15 years. Ricky Nelson was the same thing, that TV show sustained for five years. The Nelson family was very strict. I had to meet the parents, and you know, I did my number. 16 Magazine was the only one that got to him.

"Well, David's manager, Ruth Aarons, decided to go full speed ahead with David and not drag it out. I remember the first time I saw him: Ruth had told him to bring a present with him. We have these giveaway contests of stuff we collect from stars; David brought me a green-and-white high school basketball T-shirt with Number 13 on it, and some pictures. He said, 'What do you want me to do?'

"It was a great beginning. I said to him, 'you'll learn fast.'

"I liked him right away. He was shy and polite. He was like a young, beautiful green fern unfurling," which she described with long, graceful fingers. "I felt motherly towards him. I wanted to help him grow. I told him he had a duty now to do it right. 'Give it the mostest and enjoy every minute of it,' I taught him a few tricks on how to pose for the camera. I wanted to shield that tender plant from too much burning sun."

At first, she recounted, David had balked when he read some of 16's stories about him. "He came to me and said, 'Don't write all that stuff like you write, gooey stuff.' He cared too much about what his friends would think. So I said to him 'Listen, you're not Bob Dylan.' But that was just at first. Now he's on top of it. He's able to take the long view of things. He's grown into a pliable firm plant."

* * *

The airplane taxied to the terminal in Bangor, Maine, where David was due to give another matinee for 5,000 girls before his return to Los Angeles. "You cannot make a teenage idol," David was saying. "What you can do is, you can find a pretty face on the screen, like those teen magazine editors do. They'll take a kid off the street, put him in a magazine and write a lot of baloney on him, make him seem like he's busy and working and hot.

"And he'll get mail, just from kids seeing his face. They'll write fan letters. But they won't invest all their bread into, um, David Cassidy buttons, rings, posters and so on, just from seeing a picture of a guy who's cute. They're not that stupid. You can only hype them to a certain degree.

"There has to be something there. They've got to see him on television, or hear him on records, and there's gotta be something there. They can't just manufacture someone and expect him to be big and successful."

David was angry, now, at some invisible antagonist.

"I think those teen magazine editors think they're a lot more heavy and powerful than they really are." He looked out the window. "Oh no! What a bummer!" Outside, hundreds of fans stood in snow, waving banners expectantly. "Look at all those fans," David moaned. "Standing out there in the cold, waiting for me. I feel rotten, I look terrible. After a weekend of killing myself, I have to show up and smile. I can't handle it. I ain't going. I'm staying right here." David sat with his arms folded across his chest, staring out the window. The men in the band filed past him, out to a waiting bus. Ron, Henry and Steve were ready to go.

"Well," said David, softening, "I suppose I should put on my coat."

NOTE:

Annie Leibovitzs photos of David that appeared in the paper copy of the April 11, 1972 edition of Rolling Stone Magazine were not reproduced in this online version.

There are only THREE issues of "Rolling Stone Magazine" that ever sold out. The very first issue, the one with John Lennon after his death and THIS ONE!

Below is the front cover of the original Rolling Stone Magazine that featured David.