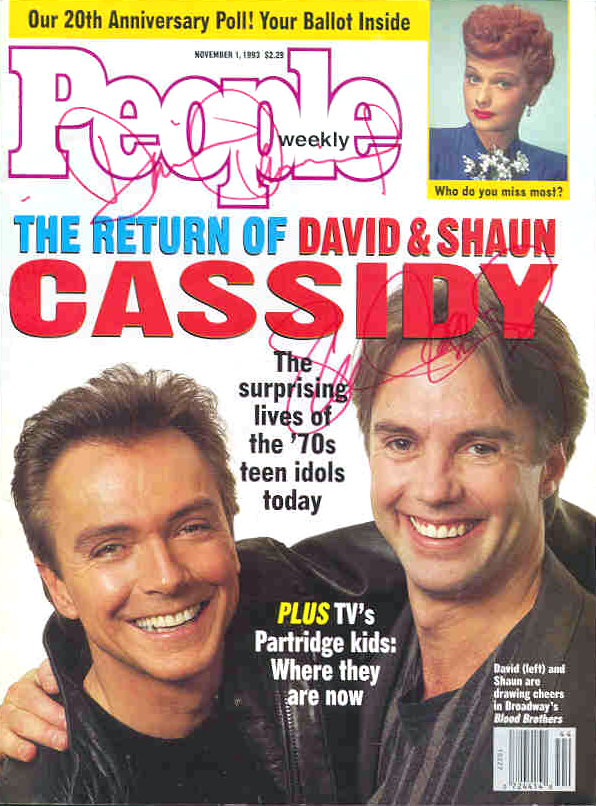

People Magazine - The Boys Are Back

November 01, 1993

Click on the image to see a larger page.

The Boys Are Back

Ex-Teen Throbs David and Shaun Cassidy—Now Drawing Swooning Fans on Broadway—Took Different Routes to Happiness

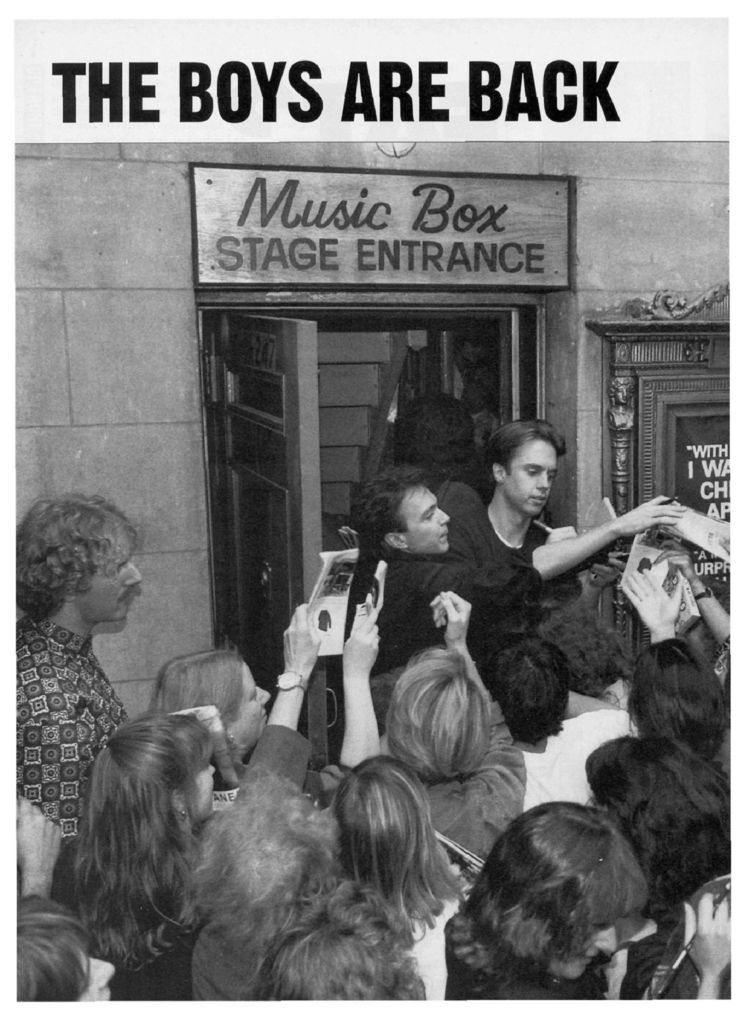

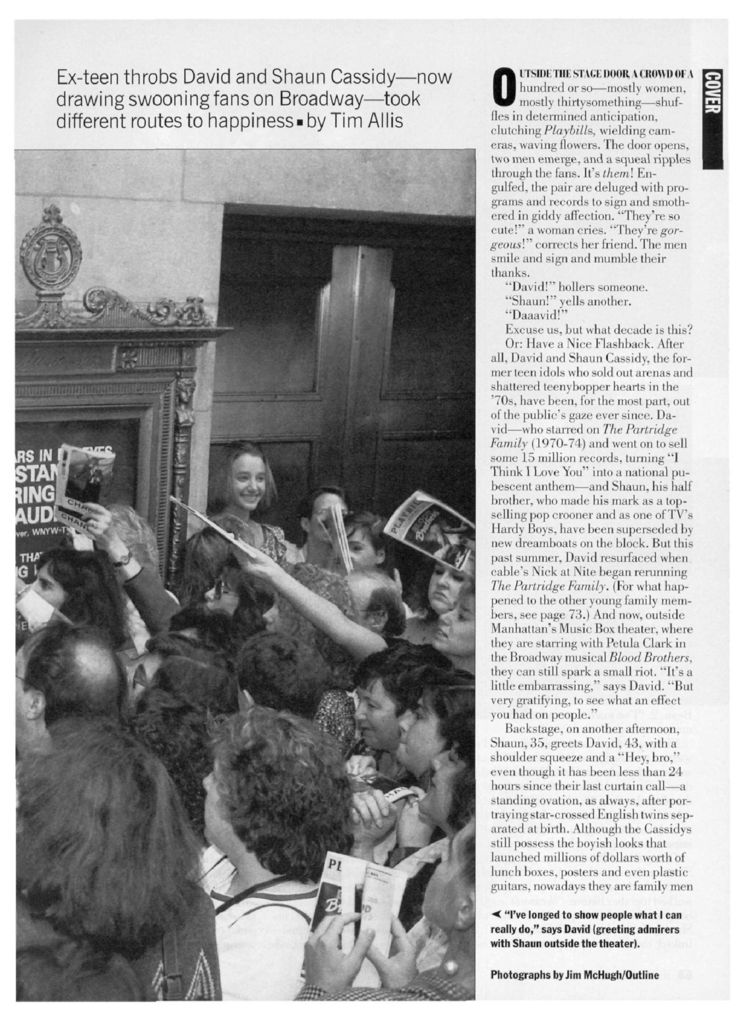

By Tim Allis and Lynda Wright

OUTSIDE THE STAGE DOOR, A CROWD OF A hundred or so—mostly women, mostly thirtysomething—shuffles in determined anticipation, clutching Playbills, wielding cameras, waving flowers. The door opens, two men emerge, and a squeal ripples through the fans. It's them! Engulfed, the pair are deluged with programs and records to sign and smothered in giddy affection. "They're so cute!" a woman cries. "They're gorgeous!" corrects her friend. The men smile and sign and mumble their thanks.

"David!" hollers someone.

"Shaun!" yells another.

"Daaavid!"

Excuse us, but what decade is this?

Or: Have a Nice flashback. After all, David and Shaun Cassidy, the former teen idols who sold out arenas and shattered teenybopper hearts in the '70s, have been, for the most part, out of the public's gaze ever since. David—who starred on The Partridge Family (1970-74) and went on to sell some 15 million records, turning "I Think I Love You" into a national pubescent anthem—and Shaun, his half brother, who made his mark as a top-selling pop crooner and as one of TV's Hardy Boys, have been superseded by new dreamboats on the block. But this past summer, David resurfaced when cable's Nick at Nite began rerunning The Partridge Family. (For what happened to the other young family members, see page 73.)

And now, outside Manhattan's Music Box theater, where they are starring with Petula Clark in the Broadway musical Blood Brothers, they can still spark a small riot. "It's a little embarrassing," says David. "But very gratifying, to see what an effect you had on people."

Backstage, on another afternoon, Shaun, 35, greets David, 43, with a shoulder squeeze and a "Hey, bro," even though it has been less than 24 hours since their last curtain call—a standing ovation, as always, after portraying star-crossed English twins separated at birth. Although the Cassidys still possess the boyish looks that launched millions of dollars worth of lunch boxes, posters and even plastic guitars, nowadays they are family men and survivors of an unusual celebrity with which they have coped in very different ways.

David's exit from performing led to years of depression and introspection. But after two failed marriages and psychoanalysis, he has found happiness with his third wife, songwriter Sue Shifrin, and their son, Beau, 2. "I've made a tremendous metamorphosis," says David.

Shaun, on the other hand, segued without trauma into a career as a TV writer and producer. He calls his children—Caitlin, 11, Jake, 8, and stepdaughter Jessica, 23, all from his dissolved 12-year marriage to former model Ann Pennington—"the most important thing in my life."

Doing Blood Brothers has given Shaun a chance to know David better; the pair had not grown up together or worked together before. "We don't have traditional sibling rivalry," says Shaun, "but we're close." They are linked, too, by their pop pasts. "We shared a mutual experience that is kind of unique," Shaun explains. "We compared notes. But I had an advantage: I saw him go through it."

"In a way, Shaun's and my lives parallel this play," says David, who portrays poor brother Mickey to Shaun's upper-crust Eddie. "My father"—debonair actor Jack Cassidy—"left and became well-to-do with my stepmother [Partridge mom Shirley Jones], and Shaun was raised in that environment." David, by contrast, spent his earliest years as an only child in a row house in West Orange, N.J., with his mother, stage actress Evelyn Ward, who was divorced from Jack when David was 3. They moved to Los Angeles when he was 11.

Shaun, the eldest child of Jack and Shirley, lionized David as "this gift" of an older brother whom he saw mostly on holidays. But he does recall that his half sibling was a bit wild. "The first time I got in a car with him, he scared the hell out of me," says the ever-cautious Shaun. For David, that venturesome streak was in tune with his times. At 16 he hitchhiked up to the hippie haven of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury. After returning to L.A. to graduate from the private Rexford School in 1968, he pursued acting, a dream since he was 3 and first saw his dad onstage.

classes while working in the mailroom of a textile company. "I wore a powder-blue smock," he recalls, "and made $38.80 a week." When he landed a part in the 1969 Broadway show Fig Leaves Are Falling, he told his boss to keep the smock—and his last paycheck.

Soon he was back in L.A., grabbing guest parts on TV. When he tested for the role of Keith Partridge in 1969, "I was 19," he says. "I wanted to pay my rent. I didn't want to become this god."

But pop deification did have its perks. "I was definitely Jack the Lad," says David. "I got to live the ultimate male fantasy, with women flinging themselves at me. I'm not bragging, just telling you." (He dated TV sis Susan Dey, but won't say whether they became serious. "[It's] in the book," demurs David, who has written a memoir, C'mon, Get Happy: Fear and Loathing in the Partridge Family Bus, due out next spring.)

Of course, many of the females who wanted to fling themselves at David were swooning over his image on their school lunch box. "Fortunately, my taste was always more toward the 30-year-olds," he says. Still, the fantasy of Keith Partridge consumed him. "I was emotionally stunted,'' he says. "I became paranoid. There were people all over me all the time."

a seemed to come to a tragic climax during his farewell concert, at London's While City Stadium, when a 14-year-old girl suffered a heart attack and died. David himself was spent. He retired from performing that year and went into a self-imposed exile followed by bouts of depression, fueled by the slow realization that no one in Hollywood could see beyond David Cassidy, pinup boy

As a result, he says, "I spent a couple of really dark, dark years." He married actress Kay Lenz in 1977, but they split in 1981. In 1984 he wed horse breeder Meryl Tanz, but that relationship lasted barely a year.

In five years of analysis, which he began in 1987, David started to examine his troubled feelings, including the resentment he fell for his absentee father, whose approval he had desperately sought. "He'd promise the moon," says David. "But he only came to one Little League game. One." When David's career began to take off, Jack was encouraging—at first. "But I think he became resentful when people began calling him David Cassidy's father," says David.

To his great regret, the two had been estranged for more than six months when Jack died in a fire in his Los Angeles penthouse apartment in 1976. David is determined that his son's upbringing will be different from his own. "I'm there for him," he says. "I keep my promises to him." Besides, he is grateful for the gift of parenthood: His wife, Sue, had been told at 40 that she couldn't have children. "He's a miracle child," she says.

Sue Shifrin first met David in 1973, after one of his shows at Wembley Stadium. The model and singer, who comes from Miami but was based in London, was invited to a party in David's penthouse hotel suite after the concert. Sue retired to the loo and returned to find that David had cleared the suite to be alone with her. "I was so angry that he presumed he could just have me," she says. Although the evening ended chastely, they later began seeing each other when David would come lo London.

Nearly 15 years later, after her marriage to a London music publisher had broken up, someone asked her who was the nicest guy she had ever dated. "David Cassidy," she said, and vowed to look him up. "He's a very caring, compassionate man, says Sue, " 'and so sweet." As a teenager in the Cassidy-Jones clan, Shaun witnessed David's ascent from up close. "I think he was envious," says his mother, Shirley Jones.

"Probably," admits Shaun. "It looked like the greatest job in the world." (Shaun's brother Patrick, 31, is a musical actor, and his other brother, Ryan, 27, works in development at Jim Henson Productions.) While he was still a student at Beverly Hills High, a family friend introduced Shaun, the aspiring rocker, to a record producer.

In 1977 he bounded onto the U.S. pop charts with a remake of the '60s ditty "Da Doo Ron Ron." Quickly he was dodging the screaming girls, à la David. But Shaun, whom his mother calls "an old soul," never took the commotion seriously. "The idea of being any kind of an idol is kind of embarrassing," he says. "My self-worth was never rooted in that."

Also in 1977, he reached a wider audience as impulsive Joe Hardy of The Hardy Boys Mysteries (opposite Parker Stevenson), which ran for three seasons. "Having a weekly schedule helped keep me grounded," says Shaun. Next he did the 1980-81 series Breaking Away and later acted extensively in live theater. Shaun's interest in writing and producing had manifested itself early on—in the late '70s he had tried to option the rights lo the book Ordinary People—but it wasn't until 1990 that he helped develop the shortlived CBS series Over My Dead Body. He went on to write and coproduce the film Strays for the USA network and has just completed a TV sequel to the Robert De Niro-Charles Grodin film Midnight Run.

In 1979, when Shaun was a mere 21, he married Pennington, several years his senior and the mother of then-9-year-old Jessica. They divorced last year. "Sometimes the harder you try to hold on, the more difficult it is," he says. Shaun, who lives alone in the San Fernando Valley, sees his children almost every week. "I take being a father more seriously than anything else," he says. He dates—but cautiously. "I'm a serial flirt," he admits. "But when I fall, I fall hard

Shaun has put his teen-star past where he says it belongs—behind him. "I thrive on change," he says. "And as I've gotten older I've become less fearful about engaging in life."

Big brother David, who continues to tour and play Partridge faves, and who scored a comeback hit, "Lying to Myself," in 1990, has taken a similarly self-possessed attitude toward his career and his life. "It's mine now," he says. "And if I screw it up, I can't get angry anymore. It feels real good."