David Cassidy on the Web

Could it be forever?

November 11, 2006

The Times Saturday Magazine

Times Online

www.timesonline.co.uk

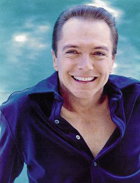

Cassidy with one of his spangled costumes from his heyday

By Janice Turner

In 1972, David Cassidy was the stuff of millions of teenage dreams until he buckled under the weight of adoration. Janice Turner meets an older, wiser fallen idol, as he prepares to strut his stuff again

We are in a taxi heading for Los Angeles airport when the publicity woman calls. Could we, by any chance, have taken David Cassidy's make-up bag? The Times photographer and I exchange glances and snigger. But the PR persists. Could it, perhaps, have got packed up with all the lights and lenses? Her teeth-clenched politeness suggests she's dealing with a situation here: David has another photo-shoot today. And having witnessed how reluctantly he faces the camera with his cosmetics, I dread to think what he's like without them.

All the way home I think about David Cassidy hunting for his "stolen" make-up bag. The image encapsulates so much about him: his defiant vanity, his (well-founded) paranoia that everyone is out to take from him and, above all, his awful, aching vulnerability. If ever there was an illustration that fame is a cruel and capricious bitch, it is a 56-year-old man, who for five years was the most desired person on the planet, with an entourage of 30 to primp his pretty face, now alone, dabbing on foundation and a slick of kohl to bring out the green of his weary eyes.

To corrupt Scott Fitzgerald's aphorism, there are few third acts in showbusiness lives. And those like Cassidy brave enough to stick around for Act III are scorned for it. "I could have killed myself and been like Monroe, Elvis or James Dean," he says, knowing how much tidier that would have been. "A legend. But I chose life."

In the age of 1,000 digital TV channels, when the music industry is fractured into a gazillion markets, it is hard to recall a time in 1972 when British girls had one simple choice: Donny or David. The Osmonds were too cheesily American, toothsome and God-bothering for sassier teen tastes. Besides, how would you and Donny ever get alone-time without the dozen other members of Team Osmond butting in? David Cassidy, however, was more with-it in his pooka-shell necklace, his hair long but not unkempt, a cheesecloth shirt unbuttoned on to an androgynous torso. He was safety and sweetness but with a homoeopathic dosage of free love. He was hippy-lite.

And Cassidy's Act I, between 1970 and 1974, was a turning point in showbusiness history. He has sold 35 million records, including three British number ones - How Can I Be Sure (1972), Daydreamer and Dreams are Nuthin' More Than Wishes (both 1973) - but the music isn't the point. I am a child of that age and can only recall - vaguely - the chirpy theme tune of his TV show The Partridge Family, I Think I Love You. Cassidy is remarkable as the first celebrity to be globally merchandised, the original one-man brand. Around $500-million worth of David Cassidy lunch-boxes, pillowcases, bubble-gum cards, even dresses were sold worldwide to a multitude of love-crazed girls who formed the biggest fan club any artist - including the Beatles - has ever had. But since his then standard contract meant he didn't own the rights to his own likeness, Cassidy received just $15,000.

The man I meet at his manager's house in Laurel Canyon is still angry about being so royally shafted. "There is no conscience in the corporate world," he says. "I was the commodity. I was the thing people were buying. But no one has ever come forward to me and said, 'Y'know, you made this company worth 100 times what it could have been. And for that you didn't make any money. So we're just going to write you a cheque. Here's $5 million, here's $50,000, here's five dollars.'"

A fairer settlement would have meant he needn't have worked so relentlessly hard in the past 15 years, doing eight to ten shows a week in Vegas throughout the Nineties. He's comfortable financially now, lives with his third wife Sue in a Hello! mansion on the waterfront in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, but I have never met anyone who seems so profoundly exhausted. Our interview is split into fragments: he can only focus for 15 minutes before he gets frazzled, wants to just chill out and smoke a cigar, his "one remaining vice".

Cassidy is 5ft 8in, but his frame is elfin. The spangled dungarees he wore on stage in the Seventies, and has brought to our shoot, fit a child-size mannequin. He had a 28in waist then (all his statistics down to his size 6 ring finger were documented for fans) and is almost as lean now. He claims not to have had plastic surgery and while the eyes seem untouched, there is a tightness about his lower face which runs out around his collar bone with a ring of loose skin. He admits dyeing his hair. I can see why he prefers doing his own make-up, not wishing to let strangers share his mortifying rituals.

What a bad fairy curse to have once been the most beautiful boy in the world. Especially since Cassidy didn't even enjoy his days of glory. Wasn't it fun to be worshipped? "That lasted about five minutes," he says, recalling the day the craziness began. "I walked into a record store at a signing before I'd ever been on TV but already my record was starting to happen. And the store expected 200 to 300 people. But there were 5,000 there and they crashed through barriers and windows. Chaos! I found it amusing for the first hour or two. But they were like 'Aaaaggghhh!'" he waggles his hands violently in my face.

Cassidy was already 20 when he signed to play Keith, the 16-year-old son in The Partridge Family, a TV show about a clan of fatherless musicians who, with their mother (played by Shirley Jones), travel America in a psychedelic van. Right from the start Cassidy felt an imposter. Keith was virginal, half-orphaned, played saccharine rinky-dinky pop. But Cassidy was a proper hippy, politically radical, a wild only-child of a bad divorce who played in rock'n'roll bands, was 17 in the Summer of Love. Growing up in LA, he picked up girls on Sunset Strip, smoked pot, hitched up to Haight-Ashbury to see the Velvet Underground and Jimi Hendrix. It tormented Cassidy that America fell in love with Keith, not David.

On YouTube there is a clip circa 1974 of him playing Rock Me Baby, where you glimpse a different David Cassidy, the one he so wanted to be. The song is raunchier than earlier hits and his voice (often speeded up slightly on his records to sound higher and younger) is deep and throaty. And peering knowingly from beneath heavy lashes, he is blatantly sexy. Does he regret The Partridge Family for taking him down the wrong path? "No longer," he says quickly and firmly. "But there was a time."

Fame turned his life into an awesome schedule. All week Cassidy recorded his TV show, scribbling songs in his lunch break which he'd record through the night. At weekends he flew across the US or abroad to give concerts.

The TV studio was his safe haven: once he stepped off the sound stage he was prey to his fans. In his first trip to Britain in 1972, 5,000 girls camped on Park Lane, serenading him with his own hits, while he remained trapped in his suite at the Dorchester. "It was insane," he says. "Surreal."

After that, London hotels declined his custom. So he chartered a yacht on the Thames, but fans only tried to swim to him, were hauled out by police and given tetanus shots. Likewise the BBC couldn't guarantee his security in the Top of the Pops studio, so he'd step out of his private jet at Heathrow, perform his song on the tarmac, then turn back for LA.

Even then Cassidy was too thoughtful, intelligent and frank to pretend fame was a blast. "I can't force a smile. It's so dishonest and it really shows," he said in 1972, when his face was kissed goodnight on millions of bedroom walls. "I just can't seem to please everybody. I feel like a loser," he lamented after his barnstorming European tour.

In truth, he was deeply lonely. "When you have people sleeping outside your house, who follow you to work, and you have to disguise yourself and you can't walk down the street, you live in this tiny vacuum bubble," he says. "And it becomes very empty and isolating."

The man who could have any woman had no time for relationships. So his minders would bring up attractive women in their twenties or thirties. He was never - thank God, given his power over prepubescents - into younger girls. "It wasn't calculated," he says. "They were banging on the door to get in." A few kiss and told, provoking legends that Cassidy was hugely well-endowed: "Well, I wonder where they got that from!" he says gleefully, making a crude pumping gesture with his fisted forearm.

But groupies were also his only connection with real life. "I was interested in them. Honestly. But they looked at me as if I was from Mars. The fact I was moving and breathing freaked them out. I was a poster on their wall who'd come to life. I'd just try to get them to relax. It wasn't 'Hi! How are you? Take your clothes off.' Just having someone to talk to who had a real life. 'What do you listen to? What do you like? What are you reading?' A lot of times it was that more than a sexual thing."

He was a fragile boy, ill-equipped for fame. Donny Osmond, who he only got to know two years ago when they shared billing on a nostalgia tour, told Cassidy he'd enjoyed his Puppy Love years, relished the female attention. "But then Donny was surrounded by his family. He was protected by his brothers and sisters," reflects Cassidy. "They gave him parameters - I had none."

David was three when his father Jack, a Broadway and TV actor of flamboyant high style, left his mother, the actress Evelyn Ward. Distraught, David listened to records of Jack's showtunes, waited beside the phone in case he called, which he rarely did. "He was the most charismatic man I ever met," says Cassidy. But his father was bi-polar in an age before effective medication. His son's sudden superior wealth and status tormented him. Moreover, Jack had married Shirley Jones, David's Partridge Family mother (with whom he had three sons including the actor Shaun Cassidy) an Oscar-winning actress and herself hugely famous.

The worship of ten million girls seemed hollow when his own father refused to express his pride or love. "I was conflicted," says Cassidy. "Because the more successful and famous I was, the more depressed and angry he became."

David Cassidy was at the pinnacle of his fame in 1974, when he brought the curtain down on his own first act. It wasn't a brave decision, he says, there was no other way. He was burnt out. His health was always fragile: he still has a nervy stomach and at 21 had his gall bladder removed. Fans burst into his room when he was unconscious after surgery, he tells me, lifting his cheesecloth shirt to reveal a 6in scar.

But it was visiting Elvis Presley, then living in LA, which made up his mind: "He had all these people around him, but I knew his life was an empty shell. He had this great sense of humour, he was a phenomenal talent, but he sold his soul to the devil. I saw myself sitting all alone like Elvis and it gave me the chills."

At the beginning of his Act II, Cassidy was still trapped in his mansion, fans camped at the gate. "I just lived in my room, played my guitar, not wanting to work, trying to figure out what I should do." With nothing in his diary he was "the ultimate single guy: I could afford to do anything. If I wanted to go some place, I could rent a plane. I was free. Free as can be. It was a world without consequences."

But being removed from reality for five years had stunted his growing up. Aged 24, emotionally he was still 19. He partied hard and unrestrained, drank heavily and tried every drug from qualudes to cocaine, although never fell into addiction. Then in 1976 Jack Cassidy fell asleep on his sofa with a lit cigarette. When he died, David and he hadn't spoken for nine months. Now the paternal approval he'd longed for could never happen.

Cassidy quickly married Kay Lenz, an actress who was also grieving her lost father. When I ask what advice he'd give his twentysomething self, Cassidy laughs and says, "Hold on, it's going to be a bumpy ride!", then adds, "Don't marry your first wife, just stay friends instead. Oh, and don't marry your second wife at all!" The second Mrs Cassidy was Meryl Tanz, a horse breeder he met when setting up a short-lived stud farm. The marriage lasted two years.

Cassidy made a couple of solo albums but was most keen to return to acting. Studio executives, he claims, wouldn't cast him out of spite, because all their teenage girlfriends had fancied him. Although more likely he was a yesterday man in the city of right-now.

Then in 1986 he ran into Sue Shifrin, a song writer with whom he'd had a brief fling during his crazy fame years. Weary of repeating his marital mistakes, Cassidy embarked on analysis three times a week and finally, he says, addressed the gaping hole in his psyche, the dad who deserted him. But David Cassidy's Act III begins properly with the birth of his son, Beau, who finally gave him something to care about beyond the vagaries of his career.

Cassidy says he wants to be the father he himself never had. He has a daughter, too, with an on-off model girlfriend from the Eighties. When Katie Cassidy was 15, her mother found her an agent and a record deal, releasing a Britney Speared-up version of I Think I Love You. David was aghast: "She was too young. I wanted to protect her as no one protected me." But now she's 19, and breaking through as an actress with the Lucy Ewing role in the movie of Dallas, he feels the paternal pride Jack Cassidy never could.

Beau's birth forced Cassidy to get out and make money again, face the indignity of making calls, pitching ideas, hustling for theatre work. He moved to Vegas, created the show The Rat Pack Is Back and in the honest daily labour of performance found, at last, something approaching contentment. Cassidy says he would swap every teenage screamer for a single night back on Broadway in Willy Russell's musical Blood Brothers (alongside his own half-brother Shaun), a gritty role where he got dirty and ugly, and was judged on his talent, not his looks.

But it is still more lucrative to play David Cassidy. He tours singing his old hits to loyal fans, women now aged 40 to 45. They don't mob him these days: "They're usually very polite. If they're drunk they can be obnoxious." To them he represents pure love untarnished by adult disappointments, and so he must strive, with his make-up bag, to resemble that boy they first adored. "I never wanted the fame. I have always tried to be someone who doesn't get noticed. I wear a hat and glasses all the time," he says. "I try to be part of our society so I can exist without being a freak."

Could It Be Forever, David Cassidy's greatest hits album, is released on Monday. He will perform in Britain in April next year on the Rewind Tour with the Osmonds and David Essex.

With his long hair and groovy good looks, David Cassidy not only sang but had his image on everything from lunch-boxes to dresses. He was at the height of his fame from 1970 to 1974, when he took himself out of the limelight

Cassiday was cast as 16-year-old Keith in The Patridge Family when he was 20, acting alongside real-life stepmum Shirley Jones, far left

Cassidy, here with Patridge Family sister Susan Dey, led an existence far from Keith's squeaky clean image - picking up girls on Sunset Strip and living a hippie lifestyle

Cassidy's half-brother, Shaun Cassidy, also achieved pop idol status in America, with hits Da Do Ron Ron and Hey Deanie, and starred in the TV series The Hardy Boys. Here, the two are pictured at David's wedding to Kay Lenz in 1976