David Cassidy on the Web

How early fame swallowed David Cassidy

The teen idol felt burnt out by Partridge Family success, longing to be taken seriously

November 26, 2017

By Joel Rubinoff

Toronto Star

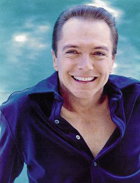

As a newspaper arts writer, Joel Rubinoff, right, got to meet his hero, David Cassidy, at Lulu’s Roadhouse in 1991.

It’s hard to explain just how big David Cassidy was in 1971, the year when — for a brief, flickering instant — he ruled the world.

It was the dawn of the ’70s, the height of long hair and hippiedom, anti-war protests and the women’s movement, Kent State and the FLQ.

But beneath the baby boom theatrics that galvanized media attention were the rumblings of a less-agitated demographic, a silent majority creeping up right behind.

These kids were too young to march to the beat of social protest and, while their older siblings rolled in the muck at Woodstock, were running around in training pants and bumping their heads on bathroom sinks.

But by 1971they were old enough to gaze outward and, as the most distended bulge of the baby boom — its peak year was 1961 — hungry for heroes of their own.

Bobby Sherman, the first of the mod-rock teen idols, racked up a few hits but — older, squarer and lacking Cassidy’s TV platform — failed to close the deal with fans. Donny Osmond was pug-nosed and infuriating, a wholesome antidote to everything pop culture stood for in the Age of Aquarius, his white teeth and perky demeanour giving him the aura of a prancing eunuch leprechaun. But David Cassidy: whoa! In the golden age of teen idols, he was the Rolls-Royce, a hero not only for legions of shrieking adolescent girls but for wannabe 10-year-old boys like me, who found winsome, windswept Keith Partridge the height of hipster cool and flocked to our TV sets every Friday at 8:30 p.m. to watch him work his magic on The Partridge Family.

Pithy, of the moment, yet weirdly anachronistic, it was the perfect showcase for the shaggy-maned pop star, who sauntered about like James Dean, minus the tortured psyche, belted out a studio-produced single every week in a crushed velvet maroon vest and ducked into flower shops to escape the hysterical teenage girls who would inevitably chase him down the street.

“Man, that’s who I wanna be!” I decided, attempting to emulate Cassidy’s diffident manner and buoyant hair flips.

When I eventually grew up and got a job as a newspaper arts writer, it was inevitable that at some point I would cross paths with my childhood hero.

But Cassidy, in person in 1991, was nothing like the Teflon hair puppet he played on TV.

Funny, insightful and endearingly cynical, yes. But sensitive. Edgy. Conflicted.

He didn’t want this, he told me. He wanted to be a rock star, like Jimi Hendrix. Or a serious actor, like his estranged dad, Jack Cassidy.

The Partridge Family was a lark that somehow got away from him.

“I was burned out from working 18 hours a day, seven days a week for five years,” he said of his 1970 to ’74 run in the spotlight.

That happy-go-lucky airhead we saw on TV asking his mom (real-life stepmom Shirley Jones) for the car keys and butting heads with his TV brother (and off-screen protégé) Danny Bonaduce wasn’t the real Cassidy. Hell, he didn’t even like the music. “The songs I was singing were not songs I would have chosen to sing,” he said with disarming candour.

“They were songs that were chosen for the character in the show. They were good. They were very good records. My taste was a little different, that’s all. Not better, just different.”

Having to sing “Doesn’t Somebody Want to Be Wanted” almost killed him: a wistful ode to loneliness that breaks in the middle for a cheesy spoken interlude.

“That was, when the song was cut, one of the only songs I stood up and said, ‘I’m not gonna do this!’ ” he said. So what happened? “They had to read me the riot act and I said, ‘Nope, I’m still not doin’ it!’ And they said, ‘You’re doing it. You’re doing it because if you don’t do it . . . ’

“And I started to think ‘Oh (bleep), I gotta work with these people for the rest of my life?’ ”

The rest of his life, it turned out, lasted four years, at which time The Partridge Family was cancelled and a relieved Cassidy headed back to semi-obscurity. He popped up now and then — a TV guest spot here, a Broadway performance there — his trademark shaggy mane intact well into the ’80s.

But by the time I ran into him in ’91, his hair was slicked back, his forehead visible and he had, he claimed, put the whole teen idol thing behind him. And yet there were, ahem, discrepancies.

Free at last to embrace his Hendrix roots and follow his sidelined theatrical muse, he instead popped up at a Kitchener nightclub in a fringed leather jacket, pumping out schmalzed-up Partridge hits and swinging his bum for a throng of hysterical women who once had posters of his androgynous face plastered on their lunch boxes.

In the end, I suspect, his early success had simply swallowed him whole, leaving nothing but a faint memory of the David that might have been.

As his 40s turned to his 50s and 60s, and we read about his alcoholism, broken marriages and bouts with depression, it became clear the crazy success of his early years had messed with his head in a way that probably wasn’t recoverable.

When he died last week from organ failure at 67, it marked the end of the imperfect life of a decent guy who achieved something truly monumental that — because it wasn’t who he really was — left him feeling unsatisfied, at odds.

But don’t feel sorry for David Cassidy. “I’ve said this a million times and I’ll sort of put it to bed,” he told me in ’91. “I never hated it. I thoroughly enjoyed the success and the impact that show had. It was a tremendous experience.”