David Cassidy: A Brief and Belated Eulogy

February 6, 2018

By Kate H

https://medium.com/@tallmank9/david-cassidy-a-brief-and-belated-eulogy-80e77b4dbd9d

“David Cassidy is exhausted, stoned and drunk” reads the opening of a 1972 Rolling Stone cover story. Cassidy viewed the cover story as a way to shed his reputation as a weightless pretty boy. The magazine viewed a cover story as a way to explore the counter-cultural staff’s complicated feelings about the most popular star and consumer product in America. Titled “Cassidy’s Naked Lunch Box” the article hovers someplace between a hit piece and empathetic portrait of teen icon. Written by Robin Green, the article is a rare early Rolling Stone article to be written by a woman, and the article’s content reflects Green’s ambivalence at being assigned (undoubtedly because of her gender) to highlight an artist who serves as a reflector of culture rather than a creator. True to its title, much of the article focuses on the kitsch products with Cassidy’s face on them, or as the article puts it “Cassidy lunch boxes; Cassidy bubblegum; Cassidy coloring books and Cassidy pens; not to mention several millions of teen magazines, wall stickers, love beads, posters and photo albums.” The listing of products is meant to cast suspicion on Cassidy’s connection to the anti-establishment music Rolling Stone regularly profiled. This suspicion is something Cassidy is well-aware of, telling Green “The magazine is very anti-me and anything I have going for me — like commercialism and all that stuff.” The fact that ABC executives made sure that Cassidy was still barely receiving any profits from these commercial items does nothing to separate him from his reputation as a crass commercial product.

When not focusing on Partridge Family advertising, Green focuses on Cassidy’s reputation as an object of lust. The article is explicit in its discussion of the sexual reaction Cassidy elicits from his teen girl audience. There are mentions of the teen girls’ “twitchy thighs” and at one point Cassidy declares “This is very filthy, but when the hall empties out after one of my concerts, those girls leave behind them thousands of sticky seats.” Once again, Green’s descriptions are ambivalent and detached. Green’s article is unusually open in her depiction of budding teen girl sexuality, but this sexuality is cast as embarrassing and crass. The article acknowledges young female sexual desire as real, but refuses to take this desire seriously.

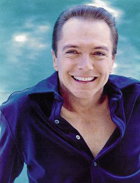

Cassidy’s sexual appeal is made most evident in the controversial photographs that accompany the article. The cover photo, shot by famed rock and roll photographer Annie Lebowitz depicts a naked Cassidy lying on the grass with his arms outstretched above his head in casual relaxation. The title “Cassidy: Nature Boy” emblazoned by his head gives the image a distinctively Summer of Love feel. Forty-Five years later, and the Lebowitz image remains striking and somewhat shocking. There are many reasons for the image’s lasting impact — the fact that twenty-two year old Cassidy still looks like a teenager, the fact that exposed pubic hair still remains taboo — but ultimately, I think the most shocking element of the photograph is Cassidy’s explicit femininity. Cassidy is small and lithe, his hair is long. In the cover photo he has his arms outstretched above his head, while he looks outwards in pleasure. He looks like the receiver of sexual desire rather than the aggressor. One of the most significant aspects of Cassidy’s image and appeal is that unlike many other teen idols, he is overtly sexual, but he is sexual in a passive way that our culture reserves only for women.

Cassidy’s visual femininity ties into the counterculture’s then disdainful belief that he exemplified the most shallow and consumerist elements of girlhood. It’s an opinion of which David Cassidy is acutely aware. In the article, Cassidy talks about his struggle to be taken seriously as a real musician instead of a pin-up boy. He talks about how a snide remark about him from a previous issue of Rolling Stone affected him. “It put a knife into me..And I bled. I went omph, that hurt.” “So I’m very defensive about Rolling Stone,” he elaborates. “I guess that’s kind of a fucked way to be [..] but I would really dig reading something about me that wasn’t, you know, the same old bullshit.”

If Rolling Stone was so dismissive of Cassidy why did they chose to make him the cover boy of their May 1972 issue? Why did they assign their most celebrated photographer to shoot Cassidy in a pose that was meant to provoke? Rolling Stone probably made these decisions for the same reason ABC refused to give Cassidy the sizable profits from his highly successful TV show. Rolling Stone and ABC wanted to exploit Cassidy’s image without acknowledging his personhood or autonomy. Rolling Stone was happy to mock the usage of Cassidy’s face to sell products, but ultimately the magazine chose to use him for the same exact purpose. As I re-read Green’s depiction of Cassidy I wonder if maybe her detailed depictions of “sticky seats” and “twitchy thighs” missed the point. The teen girl attraction to Cassidy wasn’t just about of lust; it was also about identification. Much like the girls who adored him, Cassidy was an object to fetishize, but he was never allowed to take control of his own life.