David Cassidy on the Web

David Cassidy… Behind The Scenes

Some will tell me that David Cassidy was their first crush, back when he was starring on “The Partridge Family” on TV, recording regularly, and selling out huge concert stadiums.

January 1, 2020

By Chip Deffaa

Editor-at-Large

http://www.theaterscene.net/columns/david-cassidy-behind-the-scenes/chip-deffaa/

David Cassidy’s autobiography “C’Mon Get Happy”–which I ghost-wrote for him at his request–has now come out as a Kindle E-book, with a brand new afterword by me. (It’s available for purchase on Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Cmon-Get-Happy-Partridge-ebook/dp/B07Z5NS256/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=c%27mon+get+happy+kindle&qid=1576800603&sr=8-1.) It’s selling briskly. (As I type these words, it’s #4 among Kindle books in the category “Music business.”) And I’m already getting messages from fans–finding me via Facebook and elsewhere—along the lines of: “Tell me things about him that most people don’t know, things that aren’t in the book.”

Some will tell me that David Cassidy was their first crush, back when he was starring on “The Partridge Family” on TV, recording regularly, and selling out huge concert stadiums. And they’ll write me how lucky I was to have been able to hang out with him, and how much fun he must have been. And maybe they’re remembering watching him on “The Partridge Family” on TV. And they’ll ask: “What was David Cassidy really like?”

As a policy, I don’t respond to such individual messages from strangers. Years ago I used to always respond, but I soon learned that if you answered one question, there’d always be another; and fans would keep pressing me to confide in them things that David–who was generally pretty open–was actually private about. (And David still has strong fan clubs, so there are always more fans with more questions.)

David told me many things he did not want included in any book; I’ll take those stories to my grave. He also shared many more stories that weren’t private but simply did not make the published book for reasons of space. The manuscript that I originally submitted to the publisher was about twice as long as the published book. Editor Karen Kelley did an amazing job trimming the text. And there were many more stories that simply did not make the original manuscript I submitted. David had a boundless supply of recollections.

Since his passing in 2017–due to liver and kidney failure, stemming from his alcoholism–I’ve often thought of David. I’ll recall comments he made to me, or I’ll review old notes, transcripts, and tapes of our conversations–and sometimes words he uttered so casually to me years ago will take on added significance now.

So today I’d like to share here a few more more recollections and observations. (And some photos, too–including some never before seen.) This is my way of responding to the inquiries I get from fans. David was an interesting and talented–if troubled–fellow; I like remembering him. I’m still bothered by, and saddened by, his death. I’m still trying to make sense of it all.

* * *

David Cassidy and Chip Deffaa

Here’s an example of something that David Cassidy told me which didn’t have any great significance for me at the time–but now seems quite insightful. David said that when he first met Elvis Presley in the early 1970s–when David was in the early stage of his career and Presley was in the final stage of his career–David quickly sensed an undercurrent of sadness and loneliness in Presley, feelings which David said he also often felt and tried to conceal from the public (just as he believed Presley did).

David said he looked at Presley and thought that he was looking at his own future. Those words, which David said so casually to me 25 years ago, now seem haunting. Because David–just like Presley–would go through periods of retreating from the world into his own cocoon-like home, and David–like Presley–would battle with substance-abuse problems that would ultimately cost him his life. Looking at Elvis Presley in decline, David said he felt like he was looking at his own future; and in a way, David was.

On a lighter note, David told me that the first time Presley called him out of the blue, David was sure that it could not really be the legendary Elvis Presley on the line; he was certain it had to be some prankster doing a good imitation of the easy-to-imitate Presley. And when Elvis told David, “My little girl, Lisa Marie, is a big fan of your ‘Partridge Family Show’; would it be all right if my wife brought her to the set to meet you?,” David said OK only because he was sure he was being pranked.

But several days later, Elvis Presley’s wife, Priscilla, brought their daughter, Lisa Marie (who was then just maybe three or four years old) to the “Partridge Family” set–where she interrupted the taping by running up and sitting on Shirley Jones’ lap. They had to take a break in shooting, just to accommodate the visit of Priscilla and Lisa Marie Presley.

Years later, a grown-up Lisa Marie Presley recorded an album called “Now What?” Listen to the track titled “Raven”; it not only incorporates a hint of the melody of “I Think I Love You” (David’s first big hit with the “Partridge Family”)–it actually includes a bit of three-year old Lisa Marie singing “I Think I Love You” (with her mother, Priscilla, encouraging her: “Sing it right!”), dubbed from a home-made family tape recording, So there’s a bit of a David Cassidy song on a Lisa Marie Presley album–a corroboration, of sorts, of David’s recollection.

David said that when he got to see the aging Presley in concert, he was actually disappointed. The performance struck him as slick and mechanical, lacking the fire and conviction of the early recordings that had made Elvis “The King”and–at his peak–the number-one individual concert attraction in the world. David said he watched a tired, older Elvis going through the motions, singing his old hits, and thought: “I could give a better concert than that.” And David’s early concerts certainly had plenty of electricity.

David was proud of the fact that in the early 1970s, for a while, David was the biggest-selling single concert artist in the world, commanding higher fees and selling out even bigger venues than Elvis. However, the concerts that David gave in the later years of his career–like those Elvis gave in the later years of his career–were but pale echoes of what he once could do. When young David saw in the aging Elvis what his own future might be like, there was truth there.

* * *

David Cassidy on the cover of “Tiger Beat”

Of all the notables David knew, there was no one David held in higher esteem than John Lennon. And one of his favorite memories was of John Lennon spending New Year’s Eve (circa 1975-75) at Cassidy’s home, jamming with him on Beatles tunes–the two of them singing and playing guitar, and getting drunk together. David said that when he began playing one of his personal favorites among all of the Beatles songs, “Any Time at All,” John Lennon–who wrote the song–didn’t remember how it went. And then, David told me, he had to re-teach John Lennon the chords to John’s own song, so they could sing it and play it together–with David taking Paul McCartney’s part, and feeling like a Beatle for a night.

David also said John got irked at him, another time, for flirting with a girl John liked, whom David had met through John. At first David insisted to me, virtuously, that he hadn’t flirted with her at all. Then it was like, Well maybe I flirted a little. Then it was more like, I probably shouldn’t have done it right in front of John, or dedicated a song to her in concert….

But David had tremendous charm, and could–and would–flirt with anybody. He could turn on and off at will this enormously seductive quality he had. I could see him sort of flirt with fans at the stage door after a performance. The eyes would light up, he’d banter and offer compliments. And you’d see fans–male and female alike–gaze at him with obvious longing. Some would give him their phone numbers and say: “Call me.” Afterwards, maybe I’d tell him something like: “You could have had any one of those fans who stayed so long to talk with you; they would have gone home with you in a heartbeat.” And he’d respond–in a tone of voice that reminded me a bit of a little kid complaining of the unfairness of not being allowed to eat cookies before dinner: “I know. But I can’t do anything anymore. No sex! No drinking! No drugs! I’ve turned into a responsible married man, dedicated to wife and work.” And he’d talk in a way that suggested he was chafing at the bit, and wishing he could bust loose a bit. And sometimes he’d say he didn’t see the harm in simply calling up an interesting fan, and getting together sometime to talk. And he’d say he didn’t see the harm in having an occasional glass of white wine–even though he’d been told he should not drink at all. And you could sort of see him struggling between being the scamp for a bit or the sober, responsible man.

He’d recall his serious bad-boy days of earlier years with a mix of emotions. Saying sometimes that he’d acted foolishly in his hard-partying years–and wouldn’t want to relive those years, and he understood he’d been damaged by them–but stressing that he’d needed the release at the time.

David admired tremendously Paul McCartney. And it meant a lot to him that McCartney let him watch McCarney rehearse with his band, Wings. David became friends with the band. McCartney’s lead guitarist, Jimmy McCullogh. went back with David one night, to party in David’s hotel room, and wound up getting so drunk, he smashed the TV and broke his hand. David had to call Paul McCartney to say that Jimmy was now in the hospital with a broken hand, and would not be able to play guitar until it healed. McCartney was not happy about the fact that he had to postpone a major tour (“Wings Over America”) for six weeks because McCullogh had broken his hand partying with David Cassidy. David told me that McCartney blamed him, at least in part. But David also felt–or tried to convince himself–that if McCullogh had a drinking problem, that was on him; David was not responsible. But David could see how McCartney might see him as trouble–as one fellow who drank too much enabling another (McCullogh) to mess up.

* * *

There were certain friends David spoke about with me often, repeatedly, telling me about them over and over until I felt almost like I knew them. He had only good things to say about his late friend, actor/director Sal Mineo; David spoke of Mineo with unadulterated affection and respect. He’d speak so warmly of him–their closeness was one wholly positive memory in his life–I wished I’d known him. And he was shaken by the fact that Mineo had died so young, had been murdered when he still had so much to give.

David had also liked Don Johnson a good bit when they first met one another (through Sal Mineo) when they were two young “unknowns,” it pained David when Johnson–who achieved fame via television’s “Miami Vice”–eventually blew him off as a has-been, no longer worthy of his friendship. Or so it seemed to David, who felt rejection acutely. That was still an open wound, that Don Johnson had ended their friendship when David’s career faded.

David spoke often with me of a good friend from high-school days named Kevin Hunter. He liked remembering Kevin, and telling me of their antics together. He said they were both exactly the same sorts of kids; they didn’t do well in school, they got into all sorts of small-time trouble; and they drank and did drugs for fun. They were such good friends, like brothers. I remember David telling me, while we were driving along back roads out in New Jersey in my big old Lincoln Town Car, that there were no drugs Kevin ever tried that David hadn’t tried as well. And when Kevin died of a drug overdose, when they were both around 19 or 20, David said his first thoughts were: “That could have been me.” And when he went to Kevin’s funeral, he was sure Kevin’s father was thinking, as the father looked at David: “That should be David, not my son, in that casket.” David said that Kevin’s death scared him off of drugs for a good long while. (David’s peak years of fame, from around 1970-1974, were so stressful to him, though, that when he withdrew from show business for a stretch afterwards, he went overboard, drinking and using drugs.) David tried his best to make me see Kevin Hunter clearly. We stopped some place to get tuna fish sandwiches for lunch. And kept talking. He was sharing something important to him. And he insisted to me, remembering his friend who’d died of a drug overdose so long ago: “We were very much alike, inside. It’s just sheer luck that I’m alive today and he’s not.” And I sensed David’s ongoing struggles to maintain sobriety.

David would insist to me that in high school he was just a screw-up, that he had to go back for summer school after his class graduated, before he could get his diploma. And he sometimes said that he felt like he hadn’t really changed all that much since then.

* * *

David Cassidy with younger brothers Shaun and Patrick

David’s mother, Evelyn Ward, told me she did not understand why David always wanted to put himself down when he talked with me; to her it was like he was punishing himself by painting himself in such a bad light. She felt he was just a good typical kid–maybe not the greatest student in the world but not the worst, either; and if he got into his share of trouble as a teen, it was no more than a lot of kids. But David made it part of how he defined himself for life; he saw himself as someone who was just prone to screw up. And doubted he could fundamentally change.

When I told David that his stepmother, Shirley Jones, had spoken warmly and well of him to me, he dismissed it with the suggestion that she was way too kind, that she had nice things to say about everybody; and he started talking instead about how many people had walked out on him. His first two wives had divorced him, he noted. (His third wife would eventually divorce him as well.) Shirley Jones genuinely liked him; her compliments were sincere. But it was as if he didn’t want to hear them–as if he needed to deflect and change the subject when I told him she’d spoken well of him.

He spoke to me a lot about how badly his father, actor Jack Cassidy, had always treated him, making endless promises to get together with his son and then breaking them. His said his father was vain, self-absorbed, and an alcoholic, whose drinking had led to an early death. (Jack Cassidy died in fire that was probably caused, David said, by him passing out on the sofa while smoking.) He said he didn’t want to be like his father, but added that everyone who knew the father would always say to David: “You’re just like your old man.” He’d talk about how his father—whose talents as singer and actor awed him–spent years in denial about his alcoholism. And then he’d tell me that his father’s father had also had a drinking problem, and he wondered if such things ran in families. Often when he was talking about his father with me–and we returned to that subject frequently–it felt like David was wrestling with the issue of whether he was doomed to be like his father. He wanted to be better than that. He worried about that. And it was a struggle.

His father damaged him in many ways, he felt. His father’s neglect of him while he was growing up, he felt, had left him with deep-seated trust issues. And even when he was a success, his father would tell him his success was all meaningless because David had not earned that success; he did not deserve that success. David sometimes wondered if that was true. He had a lot of self-doubts. And his father sure hadn’t helped him there.

Even when his TV show was a big hit and his recordings were on the charts, and his concerts were huge successes, there were network execs who told David: “You’re nothing, a nobody, just another suit on the rack. You were an unknown when we hired you at $600 a week. We made you famous by putting you on TV in ‘The Partridge Family.’ If we had cast someone else in that role, he would be a star today, not you. You would have remained a nobody.” And David was insecure enough to wonder if it was true, to wonder if he really deserved attention, to wonder if he was simply a synthetic, manufactured star. That nagged at him. He wanted to prove his late father wrong. He wanted to prove all in the industry who’d mocked him wrong.

* * *

Signed publicity photo of David Cassidy

David definitely had talent–far more than some of the network brass initially realized. When he was cast to play Keith Partridge in “The Partridge Family,” he was cast largely because he was so good-looking. They did not know that he could sing, nor did they care. Their original plan, David told me, was to have a studio vocalist dub all of his vocals for him, while he simply mouthed the words; he had to fight to convince them to let him do his own singing. They agreed to give him a test.

For the test, David sang along to recordings by Chicago and by Crosby, Still & Nash. Wes Farrell, who was hired to produce the recordings for the show, liked what he heard and then began writing songs with David in mind. On all “Partridge Family” recordings, David was the lead vocalist. Shirley Jones sang on the recordings, too; the other singers were simply studio singers. (None of the other actors who played members of “The Partridge Family” on TV actually sang on any of the recordings at all.)

David was glad Wes Farrell liked his singing. Farrell–a terrific judge of talent–told him he had star quality. But the network brass, as David recalled it, had no idea he was anything special; to them he was just a cute “unknown” actor they’d hired for $600 a week, a good-looking, fairly inexperienced actor who would be OK for a family-oriented sitcom.

David was blessed with a sound all his own–an intriguing, immediately-recognizable, personality-filled voice. But the network had no plans to have him do any concerts. That was David’s idea. He organized the first local concerts in his spare time, getting friends to serve as backup musicians and sell merchandise, just the way any teenage musician might handle gigs for his garage band. David had no idea how quickly things would explode. Nor did the network. They’d signed him to a seven-year contract (at a mere $600 a week), giving them total control over his TV and recording work, and control of his “name and likeness.” The contract didn’t address concert work, David told me, because the network simply did not see that coming.

The whole contract turned out to be void anyway, because David was underage when he signed it by himself; and without a parent’s signature, it was not legally binding. His manager was soon able to renegotiate a somewhat better contract. Even the revised contract was not as favorable to David as it should have been–no one imagined how extraordinarily popular he would soon be–but it was better than the old contract. The new contract gave him a chance to make a little more money for his TV work. And it still let him do what he wanted, as far as concerts went.

Demand for his concert appearances grew rapidly. He and his manager were pretty much improvising the concert career. It wasn’t planned out. They hired extra personnel (musicians, roadies, security people, etc.) as the need grew.

David was a natural concert performer. He put together his own shows, and he sold the songs with everything he had–call it charisma, magnetism, that indefinable something that makes a performer shine. He was very sexy in concert–much more so than he ever got a chance to be on the wholesome “Partridge Family” TV show. His moves were sensuous, seductive. In skin-tight pants, he’d turn and shake his butt at the audience with perfect instincts. It all felt organic. (Occasionally I will hear from David Cassidy fans who say they wish he had not spoken so much in our book about his sexual experiences. Believe me, he could have said much more! He had a strong sexual drive, and plenty of opportunities; and if he acted pretty much like a kid in a candy shop, it should not surprise anyone. And his sexuality was part of his charm. A more conservative, repressed David Cassidy would not have been as effective a concert artist. I might add, David was so exceptionally good-looking, he was getting plenty of sexual propositions long before he became a star. And once he was a star, there seemed to be fans throwing themselves at him wherever he went.)

* * *

David Cassidy in front of his boyhood home in West Orange, New Jersey

At first, doing concerts were fun for David. And it was exciting hearing his recordings on the radio. (His half-brothers were surprised by his success; they hadn’t even known he could sing.) He became world-famous quickly.

But he soon came to feel, he told me, that he was no longer in control of his life. He was working nonstop to the point of exhaustion. He came to feel trapped by his very success. There were fans crowding his house, day and night. If he wanted a sexual encounter, he told me, he could simply walk out in front of his house, and there’d be fans eager to have sex with him then and there; they’d service him on the spot. But there wasn’t time for him to have simple dates and gradually get closer to someone he liked. Relationships were impossible.

David alternated between moods of confidence and moods of self-doubts. He’d never wanted to be a teen idol. It all happened very quickly. He felt like he couldn’t keep up with it all.

A lot of the work he did during “The Partridge Family” years, simply wasn’t pleasurable for him, he said. Between the TV show, recording sessions, publicity work, and concerts, there was no time to breathe. The stress, he often told me, grew unbearable. His skin erupted in acne that was masked for TGV by heavy makeup. He suffered gall-bladder attacks. He had a tumor on his back, which was surgically removed. (He believed his health problems were a manifestation of the stress he was under.)

If he wasn’t getting much pleasure from his work, he tried to tell himself, at least he was making money.

When his album “Cherish” went gold in 1971, he had no time to spend the money it was bringing in. His management handled the money. He trusted it would be invested wisely. And someday, he figured, he’d be financially set for life. And he could then get out of the business.

Fans thought he was living a dream life. But, he often told me, there was a difference between what fans perceived and he experienced.

Fans might, for example, have good memories of him entertaining them at a sold-out concert in Madison Square Garden; but one strong memory he retained of that night was that it ended with him alone–cold, miserable, and exhausted–in a crummy motel out in Queens. He had to be hidden under a fake name out at some dump in Queens; hotels in Manhattan didn’t want him as a guest, fearing damage that out-of-control fans might cause. (And hotel managers had good cause to worry; out-of-control fans wrecked cars parked outside of Madison Square Garden. That night.)

And when fans began getting injured at his concerts–and one was crushed to death by surging fans at one concert–he lost heart. And just wanted to withdraw and be by himself. He understood Elvis’ desire to lock himself in Graceland, away from the pressures of the world. He told me countless stories that emphasized how stressful being a teen idol had been for him.

I might add that when we worked on our book, David was sharing with me spoken recollections of his experiences years before. But he also shared with me many taped recollections he had made back in the 1970s, when the memories of his early success were fresh. And he also shared taped recollections from another aborted attempt he had made at preparing a book. His comments, I noted, were utterly consistent, through the years. I knew he was sharing with me how he honestly felt. He answered any questions I had, freely. We were close enough that we could talk openly. And often argue about things. And then go back to working hard on the project.

* * *

David Cassidy at the time he was appearing in “The Partridge Family”

In talking with me about his “pop idol” years in the 1970s, David would get very critical of himself for losing all of the millions he made. He not only went broke, he told me; at the low point he was actually $800,000.00 in debt.

I told him I admired him for somehow digging himself out of an $800,000.00 debt and attaining financial stability by his 40s. I knew the hard work he’d put into achieving that, and I respected his persistence, drive, and grit. But he’d tell me: “It doesn’t matter how much money I might make now. I’ll just lose it again. I can’t hold onto money.” Those self-doubts kept resurfacing.

He’d voice occasional regrets, remembering opportunities he’d missed for one reason or another. One example. He said that the “Hardy Boys” TV series was conceived as a vehicle for David and Shaun Cassidy–two real-life brothers who would be playing brothers on TV. Shaun agreed to do the project and it proved to be a terrific opportunity for him. But David was in a funk at the time, and was feeling burned out on show business, and he told his manager (who was also Shaun’s manager) he wasn’t interested. The role went instead to Parker Stevenson (who did an excellent job), and the series was a hit. David could only wonder “what might have been?”

David recalled another time when a major corporate sponsor said they were going to present him in an hour-long network TV special. This was a huge opportunity for him. I forget who the sponsor was just now; but they made some wholesome product, like breakfast cereal or soda pop, and they wanted him associated with their brand because they liked his wholesome work on “The Partridge Family.” And then David agreed to do an interview with “Rolling Stone” magazine, cheerfully welcoming their writer into the home he shared with a friend, Sam Hyman. He was so used to complimentary feature articles, it never occurred to him that the writer might somehow harm him. He spoke with her in an open, unguarded way, trusting she’d write a complimentary piece.

But she wrote the article in such a way that he came off sounding ridiculous–shallow, superficial, jaded. She wrote that she smelled pot in the air. (David insisted to me it was Sam’s pot, not his; but that hardly mattered.) And she noted that the man David shared his home with (Sam) was sunbathing nude, out back, while they chatted–leaving readers to draw whatever inferences they wanted. “Rolling Stone” splashed on the front cover a photo of David that showed more skin than anyone had previously seen in a photo of him. And suddenly the major sponsor decided David was no longer “wholesome”–and the special was cancelled. David tried to say he didn’t care; he was tired of being perceived as “wholesome.” But it bothered him that he’d lost the chance to star in his own special. And it bothered him that he came off looking foolish in the pages of “Rolling Stone,” which he respected.

And there were assorted other things he second-guessed himself about. He licked his wounds, and went on the best he could.

* * *

David Cassidy talking with boys from the West Orange High School

In his 40s and 50s, David made good money on Broadway, in Las Vegas, and in concert appearances. He became a huge draw in Las Vegas, and Harrah’s also presented him at various venues throughout the country. He had a strong work ethic. And grabbed whatever work was offered.

He continued recording, from time to time, throughout his life. He’d disappear for a while and then come back. And he kept surprising people who’d written him off. In 1990, for example, he made the American top-40 with his single “Lyin’ to Myself.” (He was then 40 years old, and considered “yesterday’s news” in the youth-oriented recording industry.) And in 2001–when he was 51–his album “Then and Now” went platinum; it returned him to the top-five of the UK album charts for the first time since 1974. (That surprised him as much as anyone else.)

He worked hard on his post-“Partridge Days” albums–not just singing but playing piano and guitar, writing songs, producing. In later years, he liked the idea of recording old-school, the way Sinatra and Bobby Darin and others he admired had–going into a studio and recording “live” with musicians in the studio at the same time. (That’s the way he recorded his “Touch of Blue” album–taking care to record at the same studio where Sinatra had recorded so many classic numbers; he respected the tradition and wanted to feel, in some way, connected to it.)

He would throw himself wholeheartedly into a project, with a ferocious kind of tenacity. He said that was the “Aries” in him–that desire to charge full steam ahead, despite any obstacles.

* * *

He struggled with his various demons all of his life. He had a lot of unhappiness in him. He told me he felt he’d lost the ability to feel pleasure. (I’ve known many celebrities. I’ve never known anyone else who got as little satisfaction from his achievements as David did. ) I’d watch David interact with fans who clearly adored him. I saw fans tell him things like “I envy you,” or “You live a perfect life,” or “I wish I could be a success like you.” And sometimes he’d respond, lightly, with words to this effect: “No, you don’t! You don’t want my life! You’re probably much happier with your own life.” I’m sure they thought he was kidding, just making friendly, meaningless banter. But he was trying to communicate something honest and important. He’d tell them he was just another guy–and far from perfect, at that–trying his best to simply get by from one day to the next. And they’d look at him like he must be crazy. After all: He was a star, with fans. What could be better than that?

It meant a lot to him, the day we drove around his old neighborhood in West Orange, New Jersey. He stressed to me how humbly he’d grown up; he was not a child of privilege. We went to his boyhood home. He was happy to see there was still the same clothesline strung up between his old house and the house behind it–and it was still in use. (I’m sharing one black-and-white photo I took that day that has never before been published, showing him alongside of his boyhood home, with the clothesline still out back.) He told me how the neighbors directly across the street from his house raised chickens in their back yard. He told me how the “rag man” came around from time to time, asking if anyone had any old clothes, bottles, or household goods they might want to give him, that he could resell to make some money. He showed me the woods where he used to play (Eagle Rock Reservation). And we visited the shop where he used to buy toys as a child. His mom didn’t have much money, he said, and his father was often late or behind in child-support payments. But he was happier then, he said, than in all of his years as a “star.” He remembered neighborhood kids he used to pal around with, who called him “Warty.”

We went to the high school, so he could talk to the kids of West Orange. The school made a big deal of his visit–stressing to the students that he had once lived in the very same small town where they now lived, and look at how rich and famous he’d become. (He told me afterwards it was a little embarrassing for him to be held up as some kind of success story.) Kids presented him with a football jersey with his name on it. (He told me afterwards it was sort of ironic, him getting a football jersey. He could never have been a football hero. And he was the kind of slight child the football-hero types looked down on.) But he liked talking with the kids. In one of the black-and-white photos I’m sharing today, which has never before been published, we see him talking with a couple of teenage boys who were involved in theater at the high school. They were delighted to talk with him. They were in school plays. He was a bona fide star–someone to look up to. Afterwards, driving home, he told me he was glad to visit with the kids. But he just didn’t feel he was worthy of being a role model for them.

* * *

David Cassidy with father Jack Cassidy and stepmother Shirley Jones

David told me frankly that he had never wanted to have children, had never planned to have children, and had never expected to have children. He didn’t see himself as the “father” type.

But when his son, Beau, was born, he felt transformed. David stopped everything for six months just to focus on his son. Hal Prince offered him a chance to star on Broadway in “The Phantom of the Opera”–and David would have been terrific in the role–but David said no; his only interest at that point, he said, was being with his son. (He never did anything halfway. The new father was, for six months, 100% into being a father.)

When he eventually went back to work–feeling an inner need to work, as well as a financial need–he gave that everything he had–sometimes to the detriment of his family.

For a couple of years in the late 1990s, doing 10 shows a week in Las Vegas, his family saw little of him. He’d get home at one or two in the morning, long after his son Beau (then in grade school) had gone to sleep. And he’d wake up after his son had gone to school. He was making big money working so hard, but seeing little of friends and family. Finding a balance was always hard for him. It was either “all this” or “all that.”

He badly damaged one foot performing so much on an unyielding steel stage out in Las Vegas. (Broadway stages are made of wood and are carefully constructed to have some “give” for dancers. Working on an unyielding steel stage was hard on his body.) He’d get shots to help reduce the pain. And he’d go on, even when doctors felt he shouldn’t, even when he was using crutches offstage. He wanted people to feel he was reliable. He kept performing until it was absolutely impossible. He finally got his brother Patrick to fill in for him for the last performances. He got long-needed surgery on the damaged foot.

Sidelined while recovering, he asked himself what he wanted out of life. He’d built up a good bank account in recent years. But at the cost of his family life.

* * *

David Cassidy checking out the clothesline behind his boyhood home in West Orange, New Jersey

He sought help in therapy. He did not want to repeat his father’s mistakes, which he feared he was doing by spending so much time working and so little time with his wife and son.

He decided he wanted to make his family his top priority. He drastically cut back on work, doing concerts only on select weekends, trying to focus more on family. He not only attended his son’s Little League baseball games, he eventually became the coach of his son’s team. And Beau remembers David today as a great father, who was there for him when needed.. That was one goal David felt good about achieving.

One thing David definitely didn’t want for his kids was that they lose any of their childhood to show business. Both his son, Beau, and his daughter, Katie, were talented. But he did not want either of them devoting themselves to professional show business as teens. Katie at 15 wanted to commit completely to a professional career; he told her she was too young; he could not support her in that pursuing that goal, not at 15. He felt show business was too much of a meat-grinder to wish it on any teen. David felt he’d been damaged by working way too hard when he was way too young. His years on top were years of non-stop pressure; he’d had no time for reflection, for trying to find oneself, for maturing emotionally. He wanted something better for his kids. If Beau wanted to sing and dance as a youth, Beau could do it at summer camp (Stagedoor Manor, the theater camp in the Catskills). Or occasionally join his father onstage somewhere for a number. But he wanted his son to have time to explore all of his interests and “just be a kid” for as long as possible.

Fatherhood was important to David, and helped him to become less self-involved. He deliberately chose to have a home in Florida, not in the showbiz capital, Hollywood. He wanted to have a life with his family away from the spotlight.

David could be a good friend to those he trusted, and he could show kindness, privately, in many thoughtful ways. If he had money and could help a friend who needed assistance in some way, he was willing to do that. (He appreciated the way he’d been helped, at his lowest points, by one very loyal old friend, Sam Hyman, and by one cousin–not in show business–who was able to give him a hand when needed, and good counsel as well.) When one fan (who became a friend), Sian Williams, wrote him that she was hospitalized with Multiple Sclerosis, David went to the hospital and waited for hours in her hospital room until she woke up, hoping that the surprise visit would cheer her. He did this privately-things like this were never publicized. Just one human being helping another. She’ll always be appreciative. And that’s a side of David Cassidy I want to remember.

* * *

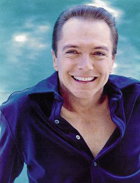

David Cassidy vacationing at the beach

David really wanted to get his autobiography out there. When he asked me to do it, he told me he liked my writing, and he trusted I could help him get the book he wanted. He was certain from the first day we began work on the book that it was going to be big–he could envision himself discussing it on “Oprah.”

To be honest, I NEVER expected the book to sell well. I liked David, but I thought he was largely forgotten. He was eager to get the book to market as soon as possible. He was always asking me how the writing was coming along, asking how soon I could get it done. (He reminded me of the little kid in the car who keeps asking: “Are we there yet?”) He wanted it done by, like, yesterday.

In the picture of David and me that you’ll see in the Kindle edition of the book (and accompanying this article) we both look relaxed and happy. But he could be a nudge, pressing me to get our book done as fast as possible, so he could promote it on radio and TV shows. He’d glance at chapters as I finished them and say he was sure the book would be a big hit. I was skeptical. I thought his moment had passed. But his hunch about the book’s popularity proved correct. The book became a surprise best-seller.

From the moment the book was released, I began hearing from fans of David. And when I got the phone call that NBC was sending a camera crew to my home here in New Jersey so that Matt Lauer could interview me about David, I realized there was still considerable interest in him. And David wound up talking about the book on “Oprah” and all of the other shows, just as he’d predicted to me. And we did some publicity together.

After years in the shadows, David Cassidy suddenly found himself–because of the book–getting heightened publicity. He liked the NBC “Headliners and Legends” profile. Then there were two Vh1 “Behind the Music” productions-one on David Cassidy himself, another on his sitcom, “The Partridge Family.” There was a made-for-TV movie about “The Partridge Family.” E! did a documentary about David Cassidy. And finally, there was a made-for-TV movie, “The David Cassidy Story “ based on our book “C’Mon Get Happy.” David served as producer. But still found parts of the finished movie painful to watch; the movie brought back more memories than he’d anticipated.

David had been hurt a lot in his life, and never fully recovered. There was a kind of “wounded bird” quality to him….. But he welcomed the renewed attention. It meant more work. It meant more money. It meant freedom to do what he wished with his time–to pursue projects that interested him, some of which turned out, others of which did not. David hoped to return to TV in a sitcom in which he would play–in drag–a hardened, middle-aged female sportswriter. He wrote the pilot and pitched it to networks, but no one could see him returning to TV in drag. I think it could have been fun. David wanted something totally different from his old “Keith Partridge” days.

But David always found things to keep himself busy. I remember checking in with him, a couple years after our book came out. And he was totally immersed in making a new album. (If memory serves, this was the album called “Old Tricks, New Dog”–which I’ll be listening to, when I finish writing this piece.) He was totally absorbed in the album. He was living, breathing, thinking it. It would have some new songs he’d written or co-written. And he’d have some old songs. And he was sure it would be his best album yet, his ultimate statement to date. And he was glad to be sort of lost in it, so completely engaged in working on it that he didn’t want to do anything else or like anything else. And I liked that quality in David, that ability (which I share) to give himself wholeheartedly to a project, and to find projects he wanted to give himself wholeheartedly to.

As for our book… he wasn’t sure he’d been wise in choosing to reveal so much in the book. He had shared with the world some things that, on reflection, he felt he might rather have shared only with close friends. There was nothing he could do about it now, he acknowledged; once you let the genie out of the bottle, there was no way to put the genie back in. And he had given his approval of the text, authorizing its publication. But wasn’t sure he should have revealed quite so much about his sex-drugs-and-rock ‘n’ roll life. Oh well. What was done was done. Everything was pretty much out there, now. He was glad the book was selling well, he noted. (But he also hoped some friends and relatives might never read it.)

* * *

David Cassidy with girls who had decorated his locker with clippings of him

David was always very ambivalent towards his Dad; he’d been hurt by his Dad’s neglect. But he always admired his dad’s talent. He’d insist to me that as a performer he could never equal what he’d seen his Dad do on Broadway. He was adamant that the greatest performance he ever witnessed by anyone was given by his Dad in the Broadway musical “She Loves Me,” which David saw when he was just 13. And he repeatedly told me the story of how he’d first seen his Dad on Broadway when he was just three-and-a-half years old. David sat in the audience with his mother. It was at the Majestic Theater on 45th Street. And when Jack Cassidy walked on stage and began singing “Wish You Were Here,” little David shouted out from the audience: “That’s my Daddy!” He could break my heart, reminiscing about his Dad.

In his last years, David began slipping into his concerts songs of his father. He began paying these little tributes to his long-dead old man. The album David was working on when he died was going to consist entirely of songs he associated with his father. I found that poignant–coming full circle, coming to the end of his life singing the earliest songs he remembered his father singing. Songs like “Wish You Were Here.” And he sang “Wish You Were Here” with such heart. He was trying, in his way, to make peace with his father.

* * *

David’s final years were grim. Arrests for driving-under-the-influence. An attempt at rehab that didn’t work. His wife left him. His health began failing. He filed for bankruptcy.

David had predicted to me, years before, that he’d eventually go bankrupt. And I think it was a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. On some level, perhaps, he didn’t really believe he deserved success, wealth, happiness, and he sabotaged himself.

The drinking, in his final years, destroyed him. (He said he drank to numb the pain he felt; but drinking did not give him any joy.) He had to give up doing concerts; he could no longer remember the lyrics. It pained me to see the deterioration in his final years. He said he’d ruined his life, drinking. He said, “So much wasted time.” He had a lot of talent; not always a lot of happiness.

I remembered him telling fans years ago that he was just another guy–far from perfect–struggling to get by from one day to the next. And I understood the truth in that.

I’m glad our book “C’Mon Get Happy” is out once again, now as an E-book with a new afterword. And I’m grateful to David’s son, Beau, for making that possible. I know–because I’m hearing from some already–there are fans who will welcome it. And I’d like to think that David would welcome the attention. (Even though he’d probably hope some friends and family would not read it.)

* * *

I want to close by sharing something that one of his friends, Elizabeth Haries, posted on her Facebook page in remembrance of David, whom she’d known for more than 30 years. She expressed so well how she felt (and I felt the same way), I just want to share what she wrote. I couldn’t express it better. And I’m glad she was able to find the words:

“Tell me it’s not true. I know it is true. My mind knows it is true. My heart will never believe it.

“How did such promise, such talent, get lost in downward spiral of self-destruction? He was amazing at fixing things for other people, but never for himself.

“He was tiny, feisty, didn’t suffer fools gladly; he liked to shock people. More articulate than he’s given credit for. Way too open–in fact, often said more than he should. Everything with him an excess . Work, get money, stop. Work, spend money, need more money. Work again until you have money. Repeat the story.

“He was hard work. Oh God, was he hard work. Story of his life. Excess and penniless, over and over.

“But through all his foibles, his career and ridiculous adulation, he could be an amazingly kind, loyal, and dependable friend. How it ended like it did I still can’t comprehend. I’m deeply saddened at his passing. But part of me is happy that he is free of this mortal coil that was for the most part a heavy weight on those tiny shoulders.

“Always, kid, always.”

– CHIP DEFFAA, December 21st, 2019