Ritz Magazine

June 1985

A young George Michael interviewed David Cassidy about stardom, struggling with fame, and doing a comeback that was published in the June 1985 issue of the Ritz fashion magazine. Below is the full transcript of the interview:

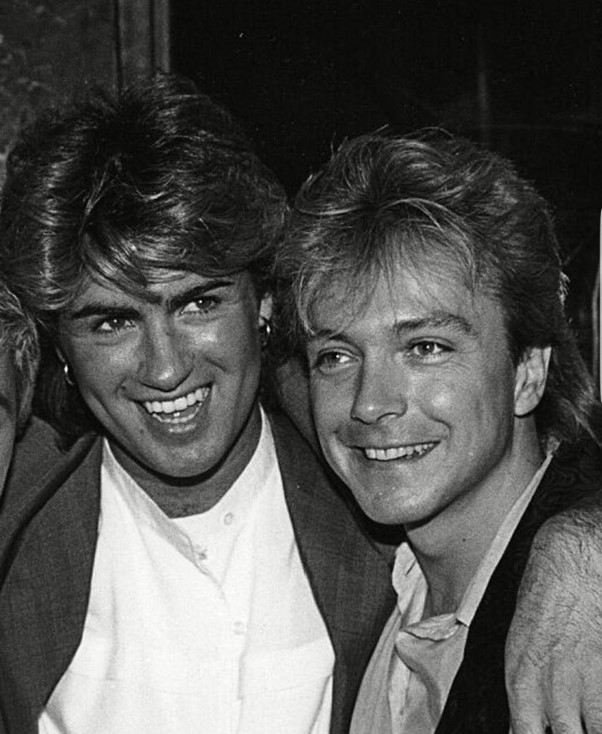

David Cassidy and George Michael

The interview between David and George first took place over lunch at Pier 31 Restaurant, at which they both got rather inebriated Ö so much so that they endeavored a second, more successful meeting at Davidís house the following week Ö.

I first met David Cassidy in early 1984 at one of Londonís more prestigious (i.e. posey) restaurants. The dinner was arranged by our mutual publisher, Dick Leahy, who told me that David was seriously considering making a comeback. (Itís a horrible word, but at least it has a ring of confidence, which is an ingredient sorely needed when approaching such a mountainous task.)

At the time, I was having a particularly hard time coming to terms with my own position in the public eye. Consequently, I could think of no reason why an artist who had seen the mayhem of the early Ď70s (which many people do not realise was a huge phenomenon in comparison to the reported scenes of Ďhysteriaí today), should want to strike up a new relationship with the music business. I was also keen to find out whether a man introduced to such a ridiculous business at a tender age of 18 (well, he looked tender, didnít he?) and subjected to all distortions for a solid six years, had actually retained his SANITY Ö

Luckily for him, and somewhat encouragingly for me, DAVID CASSIDY appears to be a well-balanced and happy individual. The effect of these six years, though sometimes very apparent, are inoffensive, even engaging, and after all he is an American.

DAVID and I have met on several occasions between that meal and this interview, weíve become friends and I think I can confidently say that, as far as the man himself is concerned, being DAVID CASSIDY is no problem at all.

David Cassidy and George Michael

GM: Have you got any plans as to what youíll do if you take off anything like the proportions you did last time? What would you do this time round? What would you do differently, because obviously you started differently, you have control?

DC: Relative control. (Laughs)

GM: OK Ė We wonít talk about last weekÖ

DC: No, we wonít talk about last week! Well, obviously itís important for me this time around that people get a true sense of who I am as opposed to a commercial sense, because I became successful last time from a TV series. I have no intentions of doing anything like The Partridge Family ever again.

GM: So, what youíre saying is basically that the last time, the personality that you were landed with was simply The Partridge Family personality?

DC: Well, when you see somebody on the TV screen and heís playing a part as an actor of this all-American good guy, who doesnít do anything wrong or use naughty words, and heís very safe and scrubs his teeth three times a day. I did a lot of that, and I think when you see him on the back of the cornflake boxes, itís difficult to get anything from that except, well this is who that person is. I think because of the kind of merchandising that was done in a blatantly commercial sense, DAVID CASSIDY was that poster that was up on the girlsí walls, and he was sexually non-threatening. I donít think I was really able ever to come through that.

GM: Donít you find that if your image was one thing, if you have been created or are part of something which creates an image, that when you try to do anything which is even vaguely upsetting to that image, even though itís really you, people see it as false, which is very frustrating, obviously?

DC: I think because of the time that has lapsed Ė in terms of eight years not making a record and not being a basically public person, I think that people are a lot more forgiving and a lot more willing to look and say, ďWell, who is this guy?Ē This album is more revealing as to who I am. There arenít a handful of poppy tunes that have nothing to do with what moves me, or where my passion is, and the songs that Iíve written on it are about that.

GM: Do you have any real worries of being taken as light pop again, or is it basically that you donít want to be seen as the teen thing again?

DC: Yes, the music speaks for itself. You let it go, and put it on the radio and people perceive it exactly how they want to perceive it. Some people might listen to this album and think, ďJesus, itís deep and itís heavy,Ē and other people might listen to it and think, ďOh no, why did I record thatĒ, which I used to do.

GM: I think the problem these days in a situation like that is that unless the music you put to those lyrics, or whatever youíre singing is blatantly non-commercial, then nobody gives a fuck what youíre singing about.

DC: I agree

GM: I think thatís probably even more the case than it was 10 years ago. I mean, you have to decide what you want.

DC: I want success again. I wouldnít be doing it otherwise. I understand the commitment to the music business. Itís two words, itís the music and now itís ďthe businessí, which is what you and I are doing.

GM: I think, having seen some reviews of the stuff, there are a lot of sympathetic ears, and there are a lot of people who would slag you off for no reason. There are also people that would give it an open ear or even a biased beneficial opinion because they have memories of you from their youth and everything, like through rose coloured glasses. I think the situation evens out in many ways, but itís got to be better than the situation you had before.

DC: Much!

GM: Which is totally created by the people. Now, letís go into something totally non-musical. Your permanent home is in LA now?

DC: I live on a farm two hours north of LA.

GM: Two hours is just outside in America isnít it? Itís like the difference between London and Manchester over hereÖ

DC: Well, itís not quite that far, but itís definitely outside; when youíre there you know youíre not in LA.

GM: Have you always had a passion for horses then?

DC: Yes, since the time I can remember breathing.

GM: They scare the shit out of me!

Dc: They scare the shit out of me sometimes too! Theyíre wild buggers, but I do have a passion for it. I love the racing. We breed them, but my real passion is, well, ultimately if anyone asked me what I really wanted in the world, I would have to say the one thing that I want more than anything else, more than an Oscar or a quadruple platinum album and single, and 15 Grammies, would be to win the Kentucky Derby. (Laughs) And after Iíd done that, Iíd probably want to win the triple crown and then Ö

GM: Would that be more important to you than having a string of No. 1 singles say?

DC: Yeah. It would be, although I look at it as two different things. Itís certainly, I think, easier to get a No. 1 single than to win Kentucky Derby.

GM: (Laughing) This is true!

DC: You know, you go in the studio with a great song, or you write a great song. Itís wonderful to get a No. 1 single. Iím just happy to be having success again. To be heard and listened and accepted again, and being back in the business, itís the first step.

GM: So, itís the first time youíve taken on such a large musical responsibility?

DC: Yeah, it is, and as somebody whoís come from the 70s, the kind of records I used to make were made me and I was just told to sing. I had very little control over what I recorded and how I sounded, so there was very little creative freedom and satisfaction when they went to No. 1, coz they werenít really mine. At least this is mine, and in the case of ĎThe Last Kiss, when I wrote it and when Iíd finished it, I felt it was the best record Iíd ever written. Itís about something very real and important that actually happened to me.

GM: I find it incredible that I can write something very personal, but when it becomes a hit record, I almost forget what I wrote it about. Itís funny how the actual public and success of the record can take things away from you.

DC: In a way it does, because then that becomes the experience, as opposed to the experience on which you wrote it. I have to keep going back to that everytime I perform it, I have to keep getting back, in order for it to be real to me.

GM: Iíve found that if I actually tried on stage, as I did at a certain point, I realized I was no longer singing about the experience, but was singing a hit record. When I go back to the experience, I get too heavily involved, and my voice starts to waiver because my mind goes, and I start to lose control. You have to strike a fair balance between the two.

DC: I never thought Iíd be saying this, but from the old days what I really savoir is standing up on stage and being able to do that. Being the focal point, you understand this as well as anybody does, being the focal point to 10, 20, 30,000 people that love everything youíre doing, they know all the songs. They canít wait for you to sing your next hit, the old ones. I have a lot of years, and a lot of hit songs that I honestly thought Iíd never sing again. Iím gonna have the opportunity to be able to sing the ones I want, because I have a lot of hit songs to pick and choose from, as well as the new stuff. Iíd never, for any amount of money, just go out and do that nostalgia act.

GM: Iíve often thought about the idea of trying to get out of the public angle of what we do, the decision you made in terms of stepping out of the limelight Ö

DC: Well, I did that Ė very drastically!

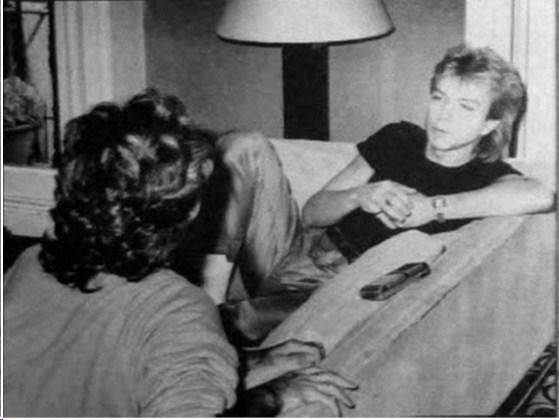

David Cassidy and George Michael

GM: Ö and saying, ďRight, Iím going to make records, but Iím not going to do all the shit.Ē

DC: You canít.

GM: Well, you can Ė you can still make records, but you canít expect them to sell in anything like the same proportions. Was there a point when you said to yourself, ďI really miss it?Ē That is the fascination for me. Every time I think itís getting too much for me, and Iím not enjoying being part of everybodyís lives. I do have to say to myself what would my real reaction be if in two years from now I hadnít been in a paper for a year.

DC: Well, after five years, of it, maybe six, I was so fed up with it, and it got to the point where it literally did take three years before I started even thinking about missing it, and thinking what fun it would be again, but I didnít want to step back into the same situation again. I wanted to be able to have that momentary hit, and be singing and performing on stage, and having that experience again. I missed that. It becomes almost like a drug. When you go on tour, night after night, you come to expect it because it happens all the time, everywhere you go. It became the only thing I ever looked forward to, actually being on the stage. Being on the road is extremely frustrating and boring. I understand why a lot of people go completely nuts. When they walk into a hotel room, theyíre so fucking crazy, they end up throwing TV sets out of the window. Itís just to break the monotony and boredom.

GM: I think to a degree, the late 60s and early 70s rock Ďní roll tour syndrome was probably a matter of people justifying their status. Normal people donít throw TV sets out of windows! The whole thing is that you are told youíre not normal Ö

DC: If you were normal, you wouldnít be doing that.

GM: I think some people canít face how theyíre written about in the most ridiculous terms, but all these terms are flattering and huge enlargements to their life, and they feel, ďOh my God, Iím just sitting here in my hotel room. Iíve got to do something larger than life. Iíll throw a TV out of the window.Ē

DC: Also in the late 60s and early 70s, youíd hear what ZEPPELIN did, and ZEPPELIN would hear about what BAD COMPANY did and what THE WHO did. It almost became like, well, I have to become more outrageous than they are. Iíve never got to the point where I was doing that, but I felt I wanted to. I guess I was just sane enough not to.

GM: If the room service was bad, youíd throw the TV set out of the window! Do you think youíll ever do anymore acting?

DC: Definitely. Yes. But not for the next year or so because of this. I spent the better half of last year putting it all together and making it happen and Iíve come all the way from nowhere to where I am now, which is a great step in one year. In order to get involved as an actor again with film Ė it takes such a commitment Ė ten to twelve hours a day when youíre working on a set. You have no time to do anything else.

GM: You have to do one thing or the other Ö

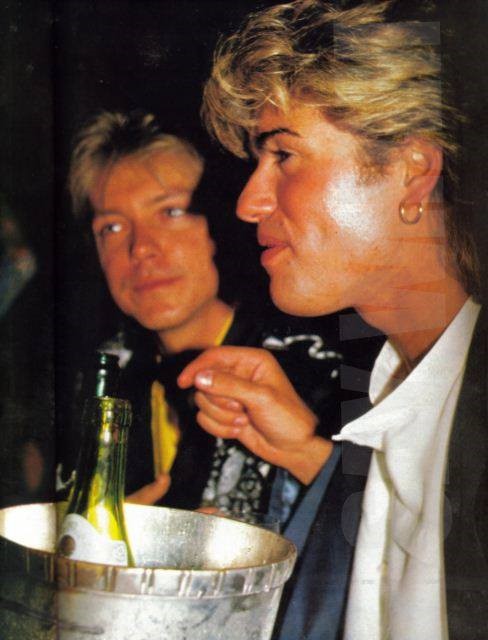

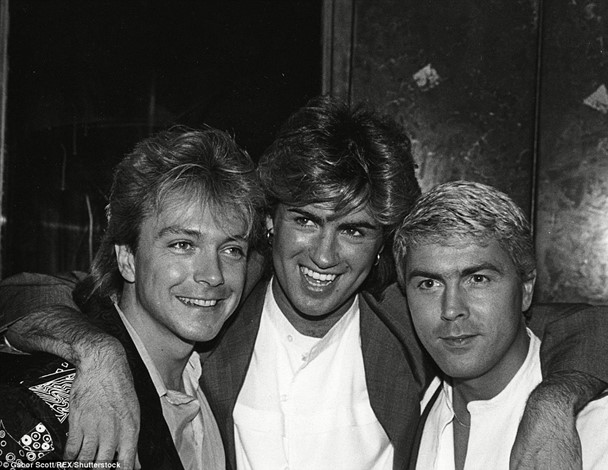

David Cassidy, George Michael and Mike Nolan

DC: So Iím going to see this album through and then go on tour.

GM: Did you find when you were doing stage work, that there was any resentment in TV and film when singers go and become actors?

DC: Not really, because Iíd come from the stage and the theatre. My first job in the business was when I was 18 years old, in a Broadway show.

GM: Did people know that and remember it? By the time youíd gone through being DAVID CASSIDY and done the Partridge Family?

DC: Well, a lot of people understood that Iíd got that part as an actor and I had done a lot of other things. I was an actor first. When I started seriously just doing anything again, I knew I didnít want to go back doing rock ní roll or making pop records again. I just knew I didnít want to go back in the studio and open that can of worms. Itís very difficult to turn that around, as you well know, the business is about momentum.

GM: If you lose it, itís very hard to get it back.

DC: Very hard. As an actor itís more difficult to get it back, than it is with one record. Iím back in it again and Iím very pleased to be sitting where I am with the album and the record. As an actor, itís going to take some time. Hopefully from this, and with people being aware that I am back in the business again, as opposed to dead, gone and buried. I think that, hopefully, the scripts that Iíll be looking to do will be coming my way. A lot of people do know that I am an actor. I donít know, itíll be interesting to see what happens in the next couple of years. But itís definitely at least a year from now.

GM: In terms of coming over here to make an LP and comeback, which makes very good sense these days with the way America looks upon England Ö

DC: I think Britain is the most important place and has more to do with influencing the direction and music and is more important than any country in the world, in terms of what is going to be successful in pop.

GM: Itís funny. Like the top 4/5 records in America this week are British.

DC: For good reason. If you hear the records that come out of Britain and America, there is a sense of climate here in Britain that there isnít in America. A few things do become successful, and in this climate, it itís good, it will be successful. You donít have to invest six million dollars into an artist like you do in America, nobody is willing to do that unless it is a proven artist and consequently there are very few new artists. When ďThe Last KissĒ was in the top ten, I looked up and said ďThank you Jesus. I can still make it!Ē

GM: Having come here and done things from a British angle, do you think in terms of the way youíve presented yourself, i.e. videos, clothes, etc. that youíve made any British concessions that you wouldnít have made in America?

DC: Since Iím a product of being here, for the best part of a year now, my taste in music, clothes and fashion has changed and Iím a lot more aware of whatís going on coz Iím confronted with it on the streets here Ė a lot more than in America. On the farm, nobody wears anything other than dungarees, wellingtons, etc.

GM: (Laughing) I used to have a great pair of dungarees.

DC: Thatís it! Iím totally removed from it over there. In America, for instance, by the time the punk thing got over there, it was very watered down. I was in the Kings Road on Saturday Ė itís a great show.

GM: It is a great show. Itís amazing the Kingís Road has kept the late 70s alive, itís all there.

Iím not gonna talk directly about your career. Right, where do I start.

DC: (Laughing) Why did you change your haircut? Oh Iím sorry Ö

GM: Everyone always asks me how many times I wash my hair! If you really want to know that, itís three times a day!! What was the longest period of time you spent out of England between the early Ď70s and now?

DC: It was quite a while. It was from í77 to í84 Ė seven years.

GM: Do you see differences Ė what do you think are the main differences that happened during those seven years?

DC: You have to understand first of all from my perspective how I viewed England. I viewed it from a limousine in the 70s or from the boot of a car, surrounded by thousands of kids and security guards on tour. So I never got into the heart and soul of England. In those days, I came over as an American sensation (I hate that word), and on News At Ten, the first day I arrived, they said, ďWe understand youíre the greatest thing from America since processed cheese!Ē I can only judge people from the media standpoint, which is TV, radio, magazines, etc. My impression is that it hasnít changed that dramatically. Only something that is controversial is worth printing. Not something that has any substance or artistic merit or creative value. The only thing thatís important is how ANDREW RIDGELEY got on last night at the Hippodrome. The only thing that really means anything to them now is if itís going to shock someone into buying it. Itís absurd. So my impression is more escapist Ė it seems now like when ANDY WARHOL, said that eventually everybody is going to be famous for 15 minutes Ė thatís his famous quote. Iím not sure how good ANDY WARHOL is or anything, except for that quote, the more I look at it, the more I find incredible wisdom behind it.

GM: I find the Americans are starting to follow the British pattern and starting to throw away people very quickly Ö

DC: Yeah, that might be, but I think probably we always have. I think it takes so much to break an artist now. With yourself, it took two years, so you know how big it is and what it takes. We try to savour and maintain it a little longer. Iím not sure that fans and the record buying public is as fickle as the media, Iím not so sure that they would want to continue to buy peopleís records if the record company didnít dictate and the radio didnít dictate.

GM: Yes, I think radio has started to dictate in the same way. Itís frightening that PRINCE was heralded by everyone as taking over from MICHAEL JACKSON, not ďIs PRINCEĒ good for this or that reason?

DC: What kind of comparison is that?

GM: Exactly. The guy is black, heís been around for a while and heís camp. There the comparisons end. Theyíre two totally different things.

DC: Well, I donít think that MICHAELíS even camp.

GM: (Laughing) Oh I think MICHAELíS camp!

DC: No, not at all.

David Cassidy and George Michael

GM: Well, anyway, PRINCE is now being knocked down for his latest album, which I havenít heard yet, so I donít know. I think heís an incredibly talented performer. The point is, heís set himself up to be burnt out, just like MICHAEL JACKSON and now in PRINCEís wake is MADONNA, she has five records being played now on American radio as we speak. I was over there last week, and couldnít believe it. Itís like everyone is setting themselves up to be burnt out.

DC: Back to before, maybe ANDY WARHOL was right.

GM: I think itís going down to five minutes!! (Laughing) Weíve got a bit of sidetracked here havenít we! What I basically feel about England, after people say itís ten years behind America, is itís probably twenty years behind! England hasnít caught up. That is why these days being a pop star is national press because itís trivia.

DC: Itís escapism, being a pop star is really rubbish now, youíre right.

GM: I think itís always been like that. The records are what they are, whether good or bad, but being a pop star has always been rubbish. I wondered if you find any differences with the attitudes towards money? There was a huge area of time where wealth was not something to be proud of. These days wealth is in.

DC: Yeah, I know. Itís very hip. Glam rock is very fashionable.

GM: Here we are in 1985 and itís all money again. Itís realism. When the greenbacks are put in front of them, they take them. I find that very much more in America. The last time things were really glamorous I was only 13, so when I grew up, there was no respect for the rich. Suddenly Iím one of the figureheads of that and Iím rich Ö

DC: So you have to deal with it. So you have a difficult task in your life as I do, because most of my friends and people I grew up with didnít become popstars and famous, and in a way, I felt embarrassed about it and Iíve always played my wealth down. I lived in a very simple environment, Iím not a real flash person. I like to dress up and enjoy myselfÖ

GM: (Laughing) I donít see any gold medallions.

DC: Yeah, SAMMY DAVIS and I are not close friends! But you know I mean. When I made a lot of money, I was 21 and I was incredibly rich in those days. In America being 21 years old and a multi-millionaire that youíd made yourself Ė forget it. It was a joke. Nobody knew how to relate to it and I didnít either.